|

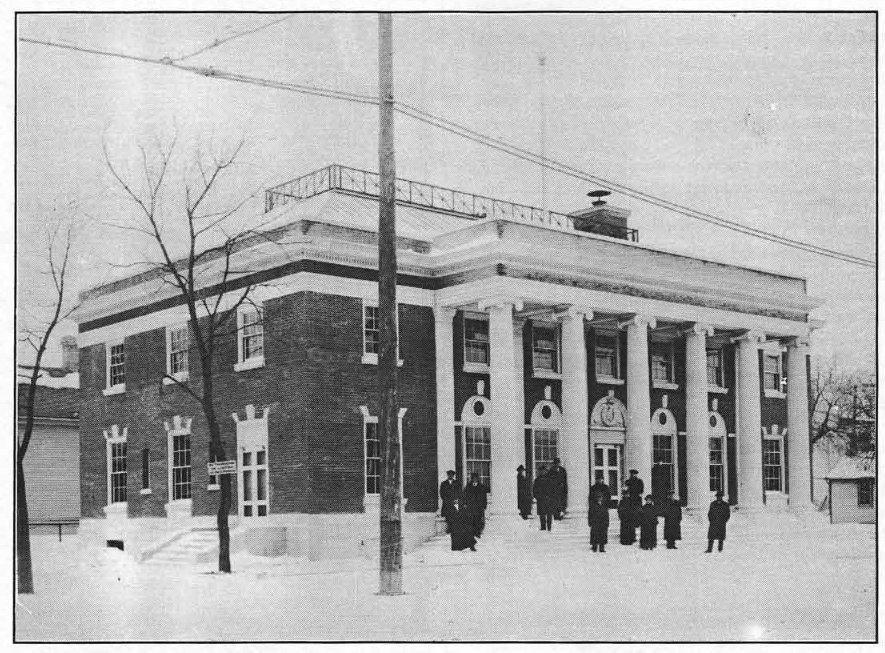

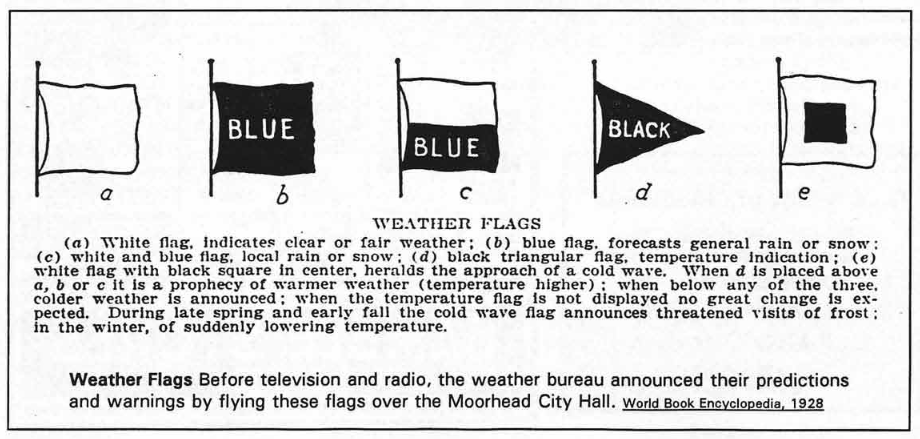

38 Days of Sub-Zero Temps: Clay County's 1936 Winter Still Coldest on Record Mark Peihl February 16, 2021 (adapted from CCHS Newsletter, January/February 1993) * * * * * * * * * * On Tuesday morning, January 14, 1936, local U.S. Weather Bureau observer Roy J. McClure received a telegraphic message from Washington at his office in the Moorhead Post Office (today The Rourke Art Gallery + Museum). A severe cold wave was approaching Clay County from the northwest. McClure quickly phoned the local radio stations and newspapers with the warning and made his way to City Hall on 5th Street and Center Avenue. McClure ran a square white flag with a black square in the middle of it up the flag pole — the weather bureau's official signal to warn citizens of a cold wave. It had already been a cold winter. November was the fourth coldest on record and the temperature had not been above freezing since December 15. Just the previous week the county had been stung with twenty-below weather. It must have been cold raising that flag. The temperature was 1°F with a 12 mile per hour wind. But little did McClure know that it would be six long weeks before Clay County would enjoy such balmy weather again. For 38 days between January 15 and February 20 the temperature at Moorhead never reached above zero, the longest such streak in the county's history. Eight times morning lows reached -30°F, twice it hit -37°F, and three blizzards added to the fiasco. It all helped to make the winter of 1936 the coldest on record. The first week of the cold snap was not that bad. Lows were around -15°F and highs about -5°F, and winds were light. Newspapers hardly mentioned the cold. But Tuesday afternoon, January 21, the bottom dropped out. By midnight the temperature was -37°F with a 15 mile per hour wind. That's a wind chill of -85 degrees. The high that day was -29°F. Few folks in Moorhead bothered to try starting their cars and fewer succeeded. Packed city buses managed to stay on schedule, but the Fargo-Moorhead Electric Street Railway routes were completely disorganized. The intense cold created a frosty film on the street car tracks. Without adequate traction it took the cars an hour to complete a 45-minute loop. Taxi cabs raced the deserted streets getting people to work and stores. Many folks waited an hour for a ride. The Fargo companies raised their fares from 15 cents to 25 cents and still did a booming business. Moorhead Judge N.I. Johnson bought a thermometer at a local hardware store, stepped outside and watched astonished as its mercury plummeted 102 degrees in moments. Most people just stayed home and talked on the phone. Northwestern Bell put on all the operators they had and could not handle the estimated 12,000 calls placed between 7:30 and 9 a.m., four times the normal load. Most of the calls were to cab companies or about school. Classes were held but attendance was off by a third. Conditions in the country were worse. Thermometers near Ulen hit -42°F and Downer residents reported -38°F for a high on Wednesday. J.B. Olsen from Hawley had to melt snow for his 16 head of stock when his well froze. Most rural schools closed for the week. Drifts blocked many township roads. A lot of snow had already fallen that winter. It was light and dry and blew like crazy with even a moderate wind. North of Georgetown WPA workers added blocks of snow to increase the height of a snow fence, but 10 foot drifts piled up anyway. On Saturday, after three days of minus thirty, the temperature "moderated" for 10 days. It even reached zero a couple of times. But on Tuesday, February 4, a strong north wind brought back frigid air. On Friday, highs edged up to -12°F and snow started to fall. By Sunday an additional 4.5 inches had fallen and blown sideways. City, state, and county road crews worked round the clock to keep main routes open, but most rural roads were clocked. The Hitterdal and Felton areas were particularly hard hit with 12 to 14 foot drifts. The Fargo Forum reported drifts "packed hard as concrete" by the wind. Crews used dynamite to clear some North Dakota roads. By Wednesday things were more under control. Then it started snowing again. Frustrated road crewmen sat as "canyons" they had spent half a day digging out fIlled in an hour with new white stuff. On Friday the weather cleared and the temp plummeted to -37°F again. The Moorhead Daily News joked that the only break Moorheadites got from shoveling coal into their furnaces was to run upstairs and phone for more coal. In Iowa, fuel became so short that armed guards were posted on coal trains. There was no such problem here. Most Clay County coal came from dock storage facilities at Duluth or open pit mines in North Dakota and Montana. Local coal dealers reported their business up by 25 to 75% over normal, but except for a couple of popular grades there was plenty to go around. However, at Hitterdal and Ulen, where snow blockedrail deliveries for a time, dealers limited what they would sell. As furnaces stoked up, chimney fires became common. Moorhead fire fighters fought three fires on one -37°F night. On Sunday, the third blizzard in less than 10 days struckand Clay County residents had had enough. The Moorhead Country Press said that old timers' stories of how cold it was in the old days were getting a lot less interesting. A Spring Prairie resident complained that his neighbors talked of nothing except coal, cold weather and firewood. With their customers marooned at home by snow and cold, merchants reported business was terrible. The previous fall male students at Moorhead State Teachers College had started a fad of going about hatless. The -30°F weather stopped that fast. Half the residents of Ulen had to haul water when their pipes froze. Although hundreds died around the country from the cold, Clay County recorded only one death. On January 22, WPA worker Gerald Payseno tried fixing a tire in a closed garage with his truck's motor running. He was overcome by exhaust fumes. Wildlife suffered terribly. Newspapers carried stories about woodpeckers frozen to trees, chickadees stuck to iron pipes, and even a rabbit found with his tongue on an ax head. Residents reported pheasants flocking in farmyards. Local game warden Robert Streich said 1936 was the worst year for wildlife he had ever seen and predicted the weather would set back pheasant production by five years. Streich pleaded with farmers to set out feed for game birds. Local Rod and Gun Clubs raised funds for bird feed. Streich himself speared 1000 pounds of rough fish at the north Red River Dam to feed pheasants. The ice on the river froze 36 inches deep and several small lakes winter-killed completely. County residents grimly dug out again and hung on. Finally, on Friday, February 21, thermometers registered at a sizzling 8°F. Soon after, 32°F weather brought a sleet storm that turned roads to ice and yet another blizzard followed, but the back was finally broken on the grand daddy of all Clay County cold waves. When the previous record for extended sub-zero weather was broken (a wimpy 11 days in 1889) the Moorhead Daily News editorialized "already youngsters of 1936 are being taught the momentous news, so that in the dimfuture when they achieve the status of grandfathers they can chuckle over a younger generation complaining about cold weather, saying: 'Now when I was a lad .... '"

3 Comments

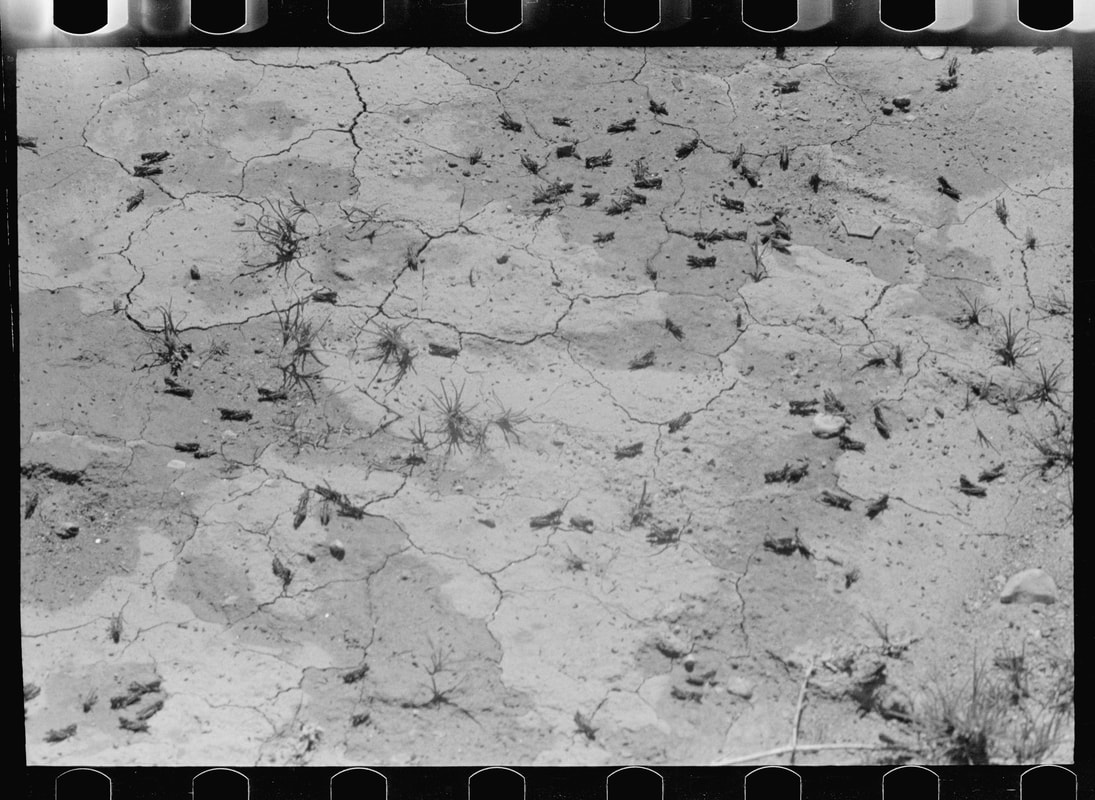

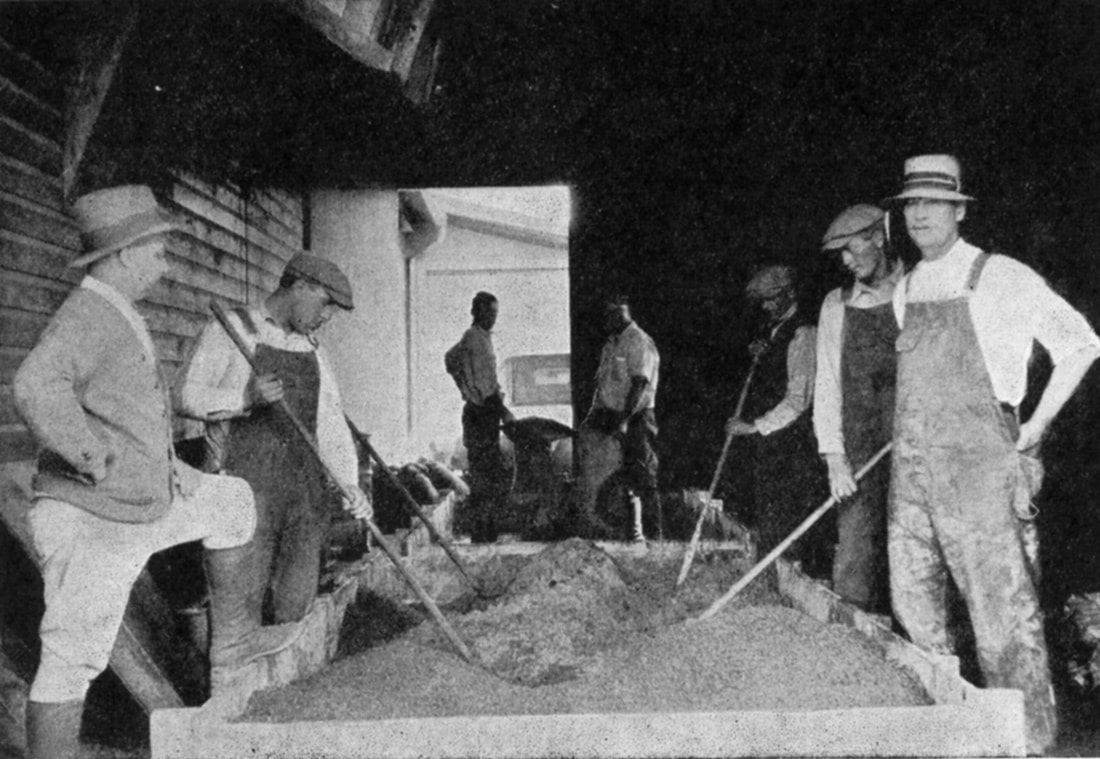

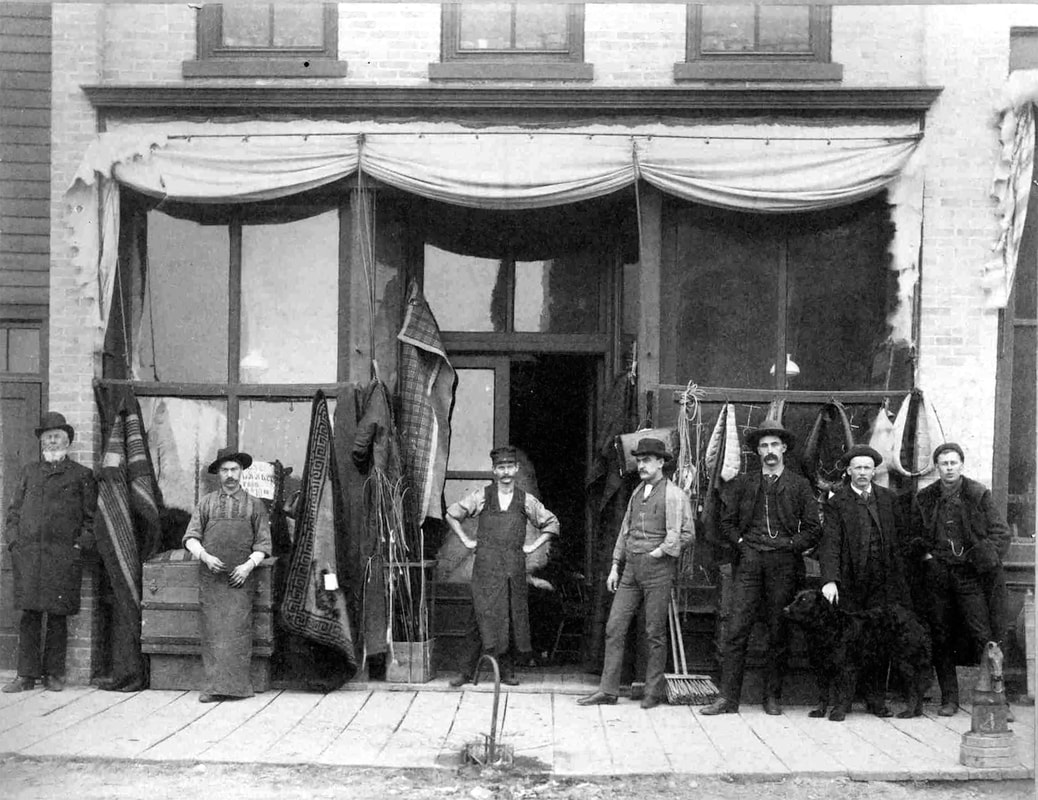

Paranormal North Davin Wait January 5, 2021 * * * * * * * * * * My good friend Matt Hopper, a talented producer with Forum Communications, first approached me about collaborating on a podcast in 2018 or '19. I frequently resisted these invitations, as I'd already spread my time fairly thin between various projects at HCSCC and some volunteering responsibilities elsewhere in the community. Of course, outside of a select few podcasts on road trips or morning walks (like Backstory or Revisionist History), I've also never been much of a podcast listener. I'm more apt to listen to public radio, YouTube documentaries, or some type of innocuous background music while I work. When I drive or workout, it's music or silence. However, when COVID-19 entered our lives in March 2020 and temporarily closed our museum at the Hjemkomst Center, my colleagues and I were forced to confront a new reality. Our positions at the museum were generally safe — which was not the case for many of our museum colleagues around the U.S. — but we needed to find new ways to connect with our audiences. So once we navigated the challenges of reopening the museum in June (before we closed again in November) and moving staff meetings and programs into digital spaces, Matt and I decided to give it a shot. Paranormal North is the result of this collaboration. We researched and scripted the episodes through August and September, both at work and in our own free time. Then we recorded and edited at WDAY studios before publishing them through inForum in October and November — just before COVID-19 visited me and my girlfriend (we're both okay). Our content drew from new research and research that my colleagues and I have conducted intermittently over the last several years, particularly for a small local folklore exhibition called Weird FM that we shared alongside an exhibition of SuperMonster市City!'s America's Monsters, Superheroes, and Villains: Our Culture At Play in the fall and winter of 2019. We wanted the podcast, like both of these exhibitions, to provide historical context and interpretation for some of the local legends in the Red River Valley. We wanted to know, what are our local legends, why do we tell these strange stories, and where do they come from? After producing four episodes we've certainly identified some ways we can improve our storytelling in this new medium, but the feedback we've received has been overwhelmingly positive. We've had thousands of listeners, and dozens of folks have reached out to share kind words or suggest upcoming episodes (we haven't decided the podcast's future, yet). Will we do a deep dive into the Kindred Lights or the Wendigo, for example? What about Nisse or Trolls? Of course, we've also encountered a little pushback, including a charge that Paranormal North deflates local legends and ruins a small slice of fun in our community. When I first read this accusation, it reminded me of valid ethical concerns I had about leading elementary and high school students on tours through Weird FM and America's Monsters, Superheroes, and Villains. I wondered, could I tactfully introduce the folklore of German and Scandinavian immigrants, including Krampus and Saint Nick, without peeling back the curtains on, say.....Santa Claus? Could I frame one of the central arguments of America's Monsters, Superheroes, and Villains — that the pop culture stories we tell and the ways we play are intrinsically tied to the material realities of history, psychology, and biology — without explicitly casting zombies, Superman, and the Marvel Universe into the shadows of the Holocaust, Hiroshima, and Jim Crow? Where do we draw these lines as journalists, educators, and historians — especially since we're not just talking about stories, but storytellers and audiences? I'm skeptical of supernatural and paranormal phenomena. I trust hard evidence and the scientific method and professional consensus. I am sympathetic to the fallibility of humans and science, and I push back against the ridicule that True Believers face, but I'm perhaps more sympathetic to the feedback I've received suggesting that magical thinking primes us for propaganda, hoaxes, and conspiracy theories. To put this another way, I personally don't think of ghosts or flying reindeer when I hear a noise in the attic, but Christmas and Halloween are still a magical time in my house. Have a listen and tell us what you think. * * * * * * * * * * Click to play/download. Episode 1 - The Vergas Hairy Man Episode 2 - The Val Johnson Incident Episode 3 - The Wild Plum Schoolhouse Poltergeist Episode 4 - The Horace Mann Elephant Paranormal North is produced in collaboration by the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County and Forum Communications. Grasshoppers in Clay County Mark Peihl October 8, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * As in the rest of the area, outbreaks of the Rocky Mountain Locust devastated crops in Clay County between 1874 and 1876. Huge swarms of the pests swept through the area eating crops, grass, trees – even laundry hung on lines. Farmers tried burning, plowing, capturing and stomping the hoppers but nothing seemed to work. Eventually they disappeared as quickly as they had appeared. Ironically, the trillions of Rocky Mountain Locusts which caused so much damage are now extinct. But five other hopper species have given local farmers fits. The hot, dry years of the 1930s proved perfect breeding environments for the bugs. Between 1932 and 1939 the hoppers caused millions of dollars in crop damage in Clay County. However, this time farmers had an effective weapon – poison. Workers mixed wheat bran, molasses and saw dust with water and sodium arsenate and spread it on fields just as the hoppers hatched. The insects ate the sweetened bran and died by the billions. The arsenic used was hazardous, causing respiratory problems, skin damage, and much worse. Unfortunately many farmers mixed and spread this grasshopper poison by hand, with little if any personal protection. Sodium arsenate was later outlawed for these purposes. In the 1980s the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency discovered 18,000 pounds of arsenic still stored on a half dozen Clay County farms. The poison was removed to a hazardous waste disposal site. How We Select Traveling Exhibitions at HCSCC Emily Kulzer September 10, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * When you visit the Hjemkomst Center or other museums, you might not think about all of the things that happen behind the scenes to make the exhibitions happen. Here is a sneak peak of the process of acquiring traveling exhibitions. As the Director of Museum Operations, one of my primary responsibilities is Traveling Exhibits Registrar. This means that I am responsible for selecting, scheduling, and shipping all of the traveling exhibits that come through the Hjemkomst Center. I am always on the search for new traveling exhibitions. There are many companies around the world who specialize in producing traveling exhibitions for museums big and small. I am subscribed to e-newsletters from a multitude of exhibit development companies and museums who travel their exhibits, so I am notified as soon as a new exhibit goes on tour and I see many that are in development. When looking at traveling exhibits there are a few different things that I think about: HCSCC’s Mission and Values Our mission is to collect, preserve, interpret, and share the history and culture of Clay County. There are very few traveling exhibits that exclusively examine or mention the history of Clay County, Minnesota. The only exceptions being traveling exhibits from the Minnesota Historical Society and other Minnesota museums. Because the options are limited, I look at different aspects of Clay County history that a potential traveling exhibit can connect to. These aspects include agriculture, the Midwest, railroad history, Native American history, Scandinavian-American history, black history, the histories of immigration, and so many more. Apart from our mission, we also have a set of values that we use to guide our decisions. Here we value diversity and inclusion, accessibility, and community partnerships. Diversity & Inclusion Clay County is very fortunate to have such a diverse community. People from all over the globe call Clay County home, as well as people from all religions, abilities, gender identities, and sexual orientations. It is very important that when selecting traveling exhibits that this diversity shows through and everyone has a chance to be represented. In the future, I look forward to booking more exhibits that examine African American history, Latinx history, the history of people with disabilities, and the history of the LGBTQIA+ community. Accessibility HCSCC has been working with Sherry Shirek, an accessibility consultant and co-founder of Arts Access for All, for many years. Sherry has taught us to be more aware of how accessible our museum is for our guests with all physical and mental abilities. If an exhibit is not as accessible as it could be, I look at how easily we can add accessible features like large font text booklets, audio description, or braille. Community Partnerships We love collaborating with other arts organizations, nonprofits, and local businesses. In the past our collaborations included sponsorships, cross-promotion of events, hiring local businesses to serve food or drinks at exhibit receptions, hosting history events at local restaurants and breweries, and volunteering. Last year, we started a partnership with the League of Women Voters of the Red River Valley to plan events for the centennial of the 19th Amendment and to include their chapter’s history in a women’s suffrage exhibit this fall. Cost The cost of the exhibit is a big part of the decision making process. Traveling exhibitions range in cost from a few hundred dollars for small exhibits to over $50,000 for large exhibits. Some of the exhibits are worth the price and some are not, so it is important to weigh the options. HCSCC is fortunate to have a nice sized exhibit budget, thanks to community sponsors and grants. Size Exhibit size is the most limiting aspect when selecting traveling exhibits. HCSCC has 5 exhibit galleries in the museum that vary in square footage and ceiling height. We can’t accommodate exhibits that require much more than 2,000 square feet in our main traveling exhibit galleries. When matching exhibits to galleries, I think about the exhibit layout and design, For example, the lower ceiling height of the 4th floor gallery creates a more intimate environment which makes it ideal for art exhibits and exhibits which might invoke deep thought and contemplation. The 4th floor gallery also offers the most security, as it can be closed off and monitored easily. The hall cases on the third floor are most often used to showcase artifacts from the HCSCC collection, poster exhibitions, and student work. Availability Traveling exhibits are always in high demand so it is important to book them early. I like to book exhibits as far as 4 years into the future. This gives us ample time to come up with supplemental programs and think of community partnerships. Programming One of my favorite parts of hosting traveling exhibits is the potential variety of programs that we can offer to our community. A new exhibit comes into the museum at least once every quarter, and that means we always have new content to base programs off of. The three major universities in the metro area provide us with an abundance of scholars who can speak on a variety of topics. Recent programs included the epidemiology of the 1918 Spanish Flu and the role of local women’s clubs in the women’s suffrage movement. Interest Lastly, and most importantly is interest. Pleasing our guests, members, and donors is one of our top priorities. If people aren’t interested in the topic, they won’t visit the museum. To gauge community interest, I pay close attention to current events, museum trends, and visitor survey feedback. With that, I would love to hear from you! Please leave me some feedback in the comments section below. What exhibits have you loved in the past and why? What do you hope to see from us in the future? Do you want more “behind the scenes” content? I look forward to reading your responses. Moorhead Woman’s Suffrage Walking Tour The Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County August 26, 2020 It's been 100 years since the United States formally adopted the 19th Amendment, allowing (many) women to vote. We're commemorating this moment by highlighting the local organizers and activists who worked for women's suffrage. Download our tour and take a walk through Moorhead history. Audio Download Transcript (PDF) * * * * * * * * * * Welcome to the Moorhead Woman’s Suffrage Walking tour brought to you by the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. This tour will take us through some of Moorhead’s most beautiful and historic neighborhoods as we learn about local women and men who were involved in the struggle to gain voting rights for American women. The stops are usually only a block or two apart and by the end of it you will have walked just about two miles. Feel free to pause this recording between stops or for breaks. First, a short introduction. The United States of America was founded as a nation that would be governed of the people, by the people, and for the people. A flier in our museum collection from Fargo Suffragist Clara Dillon Darrow asked “are women not people?” Women did not have voting rights, and by the mid-1800s, women were organizing to correct this. They called it the Woman’s Suffrage Movement, suffrage meaning the right to vote. They called themselves Suffragists, though today we tend to remember them as the Suffragettes, a word invented by their enemies and intended to be demeaning. Whether you call them Suffragists or Suffragettes, you have to admire them for changing our country for the better, and some of those American heroines lived right here in our town. The fight for Woman’s Suffrage was waged state by state. Legislators in Wyoming Territory were the first to recognize the voting rights of women in 1869. Over the following decades, Women gained full voting rights in a patchwork of mostly western states, and limited voting rights in others. But the Suffragists were persistent and increasingly impossible to ignore. On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives approved a proposed 19th Amendment to the Constitution that would make it illegal to restrict voting rights of Americans on the basis of sex. The US Senate approved it two weeks later, and it was off to the state legislatures to vote on. It needed the approval of 36 states to pass. Minnesota ratified the Amendment on September 8, North Dakota ratified it on December 4, and finally, on August 26, 1920, the Amendment became the law of the land. The Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association had branches in towns and counties throughout the state, organized by legislative district and run by women who held the title of chairmen. Legislative District 49 was centered in Moorhead and we had four or five chairmen at a time. Admittedly, the story of the struggle for Woman’s Suffrage in Minnesota is centered in and dominated by St. Paul and MInneapolis, but our Moorhead Suffragists were just across the river from Fargo, which was the center of the lively and active Suffrage fight in North Dakota. This tour relies on a list of names of women and men from our area that are found in the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association archive at the Minnesota Historical Society, but those records tell us little about what these Suffragists did in their various roles in Moorhead. So on this tour, we will not be focusing on what these people did, but on who these people were, and how they represented different aspects of the Woman’s Suffrage Movement. Time to go to stop number 1: The Comstock House at 506 8th Street South. If you’re not there yet, feel free to pause this recording until you get there. Stop 1: 506 8th St S The Comstock House Our first stop is the Comstock House, a Minnesota HIstorical Society site operated in partnership with the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. Feel free to walk around, we like having you here. This was the home of Solomon and Sarah Comstock, and their children Ada, Jesse and George. For the first half century of our town’s existence, the Comstock family was the most influential family in Moorhead, socially, economically, and politically. It is a common trend across our nation that Suffragists tended to be women of means whose families were community leaders at the top of the social and economic ladder in town, and if you are looking at the front door of the Comstock House, you can see the stately home of the most important Suffrage family in town - as long as you turn around and look at the brown house across 8th Street - Mary and Frank Peterson are the most important family of Moorhead’s Womans’ Suffrage movement - don’t worry, we’ll get to them later. The Comstocks, as far as we can tell, did not engage in the Woman’s Suffrage Movement, at least not publicly. But we stop here because while the Comstocks may not have talked the talk of Suffrage, they certainly did walk the walk of women’s equality. Sarah Comstock was a teacher before she came to the two year old Wild West town of Moorhead in 1874 and married an ambitious young attorney named Solomon. Solomon rose from county attorney to state representative to US Congressman to the business associate of railroad magnate James J. Hill, the richest man in Minnesota. This gave the family a lot of political and economic influence, and perhaps the most important way they used this influence is they turned Moorhead into a college town. Minnesota State University Moorhead and Concordia College are both here because of the Comstocks, and one of the common themes that you’ll see throughout this tour is Suffragists were overwhelmingly educated women at a time when educating women wasn’t common. Sarah and Solomon’s two daughters and one son received wonderful educations, and oldest daughter Ada became a nationally famous pioneer in the field of women’s education. It would be hard to imagine that Ada Comstock, who as president of Radcliffe College helped turn all-male Harvard co-ed, wouldn’t want the right to vote. There are buildings named for this family at Minnesota State University Moorhead, Concordia College, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Smith College and Radcliffe College. And there’s another reason we begin our tour here. In this house, in 1893, the leading women of town formed The Moorhead Woman’s Club. Two years later, the Moorhead Women’s Club would become one of the 15 charter members of the Minnesota Federation of Women’s Clubs - which would eventually grow to 500 chapters with 40,000 members. Woman’s Clubs were creative and intellectual outlets for women as well as centers of civic engagement. Each year, a club would choose a topic to study - Moorhead’s 1893 topic was Ancient Egypt, the 1906-7 season’s topic was Italian Sculpture and Painting in the Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Centuries, and the group studied Panama and South America in 1913-14. The members wrote essays, recited poems, and performed music on that theme, hosting each other in their homes on a rotating basis. Membership in the Moorhead Women’s Club was limited to 25 women plus a list of inactive honorary members, so being a member was an indication that you are a woman of culture from a well-connected family in town. It should not surprise you that many Suffragists were members of these clubs of educated, civic minded, community leaders. That goes for Moorhead or any American town. Before we leave the Comstock House, we should mention that there was an important local Suffragist in this family. Ruth Roberts Haggart was the daughter of Sarah’s sister Jennie and her husband Samuel Roberts. Ruth was an officer in the North Dakota Votes for Women League and she hosted a series of Suffrage Teas and dinner socials in Fargo to get local women interested in the movement. Our next stop is not far away. Go out the front gate and take a left to walk south along 8th Street. You’ll see a new brick building with a black sign that says Comstock Commons - 600 8th St South. Stop 2: 600 8th St S: Comstock Commons, The former site of the Esther Russell House Comstock Commons is built on top of where Esther Russell used to live. I want to say that Esther Russell is your typical Woman’s Suffrage leader, but the word “typical” doesn’t seem to apply to an impressive woman like Esther Russell. But then again, the Woman’s Suffrage movement regularly attracted impressive people. Esther was one of four chairmen of our branch of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association and she must have done a good job because on the organization’s list entitled “Prominent Minnesota Suffrage Workers,” Esther is one of only 16 people living outside the Twin Cities. Esther Russell grew up in Marshall, Minnesota, the daughter of a carpenter. She became a teacher before marrying William Russell. William became a prominent Moorhead attorney, and in American society back then, that meant his wife Esther also had the opportunity to be prominent in Moorhead society. She took that opportunity. Esther was also the head of our local chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, or WCTU. The Temperance Movement was an international movement to get people to stop drinking alcohol, and it was absolutely intertwined with the Woman’s Suffrage Movement. America in the 19th century had a drinking problem. Women got fed up with their husbands spending their evenings and money in saloons, where women were not allowed to enter, often coming home violently drunk in an era when it was difficult for women to escape abusive relationships. For their children, their sisters and themselves, many American women became politically active for the first time as Temperance advocates. Through the Temperance Movement, generations of women learned how to organize to get legislation passed. They developed working relationships with legislators, and they started getting more and more annoyed that they were not allowed to vote for these laws they were promoting. And their male allies in the Temperance Movement also knew that if women could vote it would be so much easier to get anti-alcohol laws passed. The Temperance and Woman’s Suffrage movements were intertwined a century ago not unlike how the topics of Abortion and Gun Control are today. But this merger of movements did have a downside. A lot of families, especially in Moorhead, owed their livelihoods to the alcohol industry. Local Saloon-owning families like the Kiefers, Ingersols, Magnussons, and Diemerts shared many traits of the Suffragist families on this tour: they were prominent business leaders, they were active in local politics, they sent daughters to college to become teachers, but you don’t see their names on the rolls of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association. I don’t think we should necessarily take this to mean that Emma Magnuson wanted fewer rights than Esther Russell did, but I can certainly understand if she wouldn’t want to be in the same room as the woman who is trying to make their family’s business illegal. Off to the next stop, which is 906 7th Street South. Keep walking south along 8th Street until you get to the stoplights on 7th Avenue South. Turn left and walk to the end of the block. Across the street should be a two-story cream-colored house with red trim. Stop 3: 906 7th Ave S The Anna Gates House While Esther Russell embodied many of the attributes common to American Suffrage fighters, Anna Gates was in many ways an outlier, though both served as Chairmen of District 49’s Minnesota Woman’s Suffrage Association at the same time. Anna is the only immigrant on our list of local women involved in the Minnesota Woman’s Suffrage Association. She was born Anna Liedahl in Norway. She crossed the ocean to America at the age of nine in 1881. Her family settled near Leonard, North Dakota, about 40 miles southwest of Moorhead. She moved to Moorhead after meeting and marrying a letter carrier named Elbert Gates - which is another difference between her and Esther Russell: the Gates were working class. Soon after Suffrage was achieved, Anna Gates herself went to work. She became Moorhead’s first female police officer. Her official title was Police Matron, and today we would think of her as part cop, part social worker, part city food inspector. Officer Gates was called in to handle cases where the suspects were either women or children. She also organized the city’s charity drives to provide food and clothing to impoverished families during the Great Depression. While Gates served as a chairman in Moorhead, she also did quite a lot of collaboration with the very active grassroots Woman’s Suffrage organizations in North Dakota. On October 8, 1914, the Wahpeton Times reported that she was working for suffrage while visiting her relatives back home: “Mrs. Anna Gates of Moorhead, Minnesota, who has been doing quite a little quiet work for suffrage among the farm women near Leonard reports a very encouraging prospect for suffrage in that region.” She was not a member of the Moorhead Woman’s Club, but was instead an officer in the Fargo Progressive Club. As part of that group in 1912, Anna was one of the women in charge of bringing nationally-known Women’s rights icon Jane Addams to Fargo. We’ll learn a little more about some Fargo Suffragists at our next stop - turn around and walk back towards 8th Street. Cross over to the west side of 8th at the light and keep walking down 7th Avenue south until you’re in front of two large Concordia College Dorms called Bogstad Manor East and Bogstad Manor West. Stop 4: 618 7th St S: Bogstad Manor East Formerly the Edith Darrow Godfrey House A century ago, there would have been a hospital where Bogstad Manor West is today, and Bogstad Manor East would have been a row of fine houses lining 8th Street. In one of those houses lived the founder of the hospital, Doctor Daniel C. Darrow and his wife Alice. Right next door to them, just about directly across the street of Esther Russell, lived their daughter Edith Darrow Godfrey, who was a chairman of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association. Edith grew up the daughter of one of Moorhead’s most respected families. Her father was a pioneer doctor who moved to Moorhead to join his brother, Fargo physician Dr. E. M. Darrow soon after he graduated medical school in 1884. Edith’s mother Alice was one of the founding members of the Moorhead Woman’s Club. In 1899, Edith Darrow married a promising young businessman named Joseph V. Godfrey. Joseph V. Godfrey’s name is written all over town even today, but you have to look down to see it. He had a concrete business and you’ll see his maker’s stamp on sidewalks throughout Moorhead’s older neighborhoods. We are walking on his sidewalks all through this tour. Joseph and Edith had two children - a boy and a girl. But in January of 1911, Joseph got a flu that turned into pneumonia. He died at the age of 36, leaving Edith a young widow with a ten year old son and a two year old daughter. Joseph’s obituary called him “one of the best known and best liked citizens of Moorhead.” Edith Darrow Godfrey came from one of our region’s most prominent suffrage families. Her aunt in Fargo was Clara Dillon Darrow. Clara Darrow was one of the earliest and strongest voices for Woman’s Suffrage in North Dakota, a woman who gave suffrage speeches to prairie homesteaders and was the founding president of the North Dakota Votes for Women League in 1912. Clara’s daughters Mary Darrow Weibel and Elizabeth Darrow O’Neil were also active in North Dakota’s suffrage movement, and so was their little brother Daniel. When Edith’s husband passed away, Cousin Mary, Aunt Clara, and her parents were all with her at his bedside. Our next stop is not far away. As you walk west toward the river down 7th Avenue South take a right on the first sidewalk you see. You’ll walk past the parking lot of Bogstad Manor West and on the other side of the black gate you’ll be on 7th Street South. We’re looking for a white house with blue trim: 515 7th Street South. Stop 5: 515 7th St S The Bessie Lewis House Here we have the house of Minnesota Woman Suffrage Chairman Bessie Lewis. She served as chairman at the same time as her friend and neighbor Edith Darrow Godfrey. Bessie’s husband Thomas Lewis was one of the pall bearers at Joseph V. Godfrey’s funeral. Tom Lewis sold wholesale groceries. Bessie was a teacher. Census records indicate that she may have taken some time off of teaching to raise her three children, but by 1920 both she and her youngest daughter Flora, a recent graduate of Moorhead Normal School, were both working as teachers. Being a teacher was a common profession for Moorhead’s Suffragists, perhaps not surprising since the primary purpose of Moorhead Normal School was training teachers. That school is now called Minnesota State University Moorhead, and it still trains a lot of teachers. Bessie was also an accomplished embroiderer. She won two first prize ribbons at the Minnesota State Fair for her embroidery. On September 8th, 1919, the Minnesota Legislature voted on a proposed 19th Amendment to the Constitution that would make it illegal to restrict an American Citizen’s right to vote based on their sex. Bessie and Thomas Lewis had a big party at their house that day, but not because Minnesota ratified the amendment. That day also happened to be their 25th wedding anniversary, and about 20 of their friends and neighbors threw them a surprise party. To reach our next stop, keep walking to the end of the block and take a right on 5th Avenue South. When you reach 8th Street, the large brown and stucco house on your right will be 721 5th Avenue South. Stop 6: 721 5th Ave S The Mary B. and Frank H. Peterson House You’ve seen this house before when you were standing at the entrance of the Comstock House. This used to be the home of Mary B. Peterson and her husband, Minnesota State Senator Frank H. Peterson. The house is now split into apartments and the building’s entrance has changed from the Peterson’s front door facing 8th Street to their side door on 5th Avenue. Mary Peterson was one of the four district chairmen of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association and a frequent donor to the cause. She was one of the founding members of the Moorhead Woman’s Club in 1893. And her husband Frank was a leading Progressive in the Minnesota State Senate. Most of this tour has been talking about how regular people in a prairie town played a small role in the larger fight for voting rights, but this house is the exception. In 1922, after voting rights were won, the National Woman Suffrage Association published an official six-volume history of how it all happened. The chapter written by the Minnesota Suffragists singles out Senator Frank H. Peterson as being one of the most important legislators working on behalf of Woman’s Suffrage - the most important being Otter Tail County’s Ole Segang, whose nickname at in St. Paul was “The Napoleon of Woman’s Suffrage.” Senator Peterson’s work for suffrage was related to his life’s calling of getting people to stop drinking alcohol. It is likely that Senator Peterson worked hard to give women the right to vote because he believed it was the right thing to do, but politicians like Peterson also hoped that women would add votes to the Temperance cause. The jury is out over whether the Temperance cause helped Woman’s Suffrage or hindered it. To use modern political jargon, it brought out the base but it also energized the opposition. Fearing women voters would bring about Prohibition, the liquor industry fought tooth and nail to prevent women from gaining the right to vote. Senator Peterson saw Woman’s Suffrage bills come before the Minnesota legislature five times between 1909 and 1917, and each time the Suffragists lost by only four or fewer votes in the senate. Each time the opposition to the bills was led by senators connected to the liquor industry. But in January of 1919, the passage of the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution made alcohol illegal throughout the whole country and brought about national Prohibition. As soon as Woman’s Suffrage was uncoupled from the alcohol debate and could be considered on its own merit, the Minnesota Legislature had a profound change of heart. Minnesota approved the proposed 19th Amendment that would end voting discrimination against women by a margin of 100 to 28 in the House and 49 to 7 in the Senate. For our next stop, turn west toward the river and take a right on 7th Street South. Walk north two blocks and the next stop will be on the right side of the road: 310 7th St S Stop 7: 310 7th St S The Jenny Briggs House This was the home of Jenny and Francis Briggs. Jenny was one of five Chairmen of our branch of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association, serving with Anna Gates, Edith Darrow Godfrey, Bessie Lewis and May Burnham, who you will meet next. Jenny’s husband Francis was a physician. This family wasn’t in town for too many years, but they were important years. They were here in 1920 when the 19th Amendment finally achieved Voting Rights for Women, and they were here for the world-changing event that went a long way to making the 19th Amendment possible - I’m talking about World War I. Americans have forgotten just how important and life-changing World War One was to our ancestors. To those who lived through it, WWI was a defining moment of a generation, the biggest challenge our nation faced since the Civil War fifty years before. The leading families of each American community were expected to step up and lead their town’s war effort on the Home Front. And as we have seen so many times already, Woman Suffrage families were Moorhead’s community leaders, and they stepped up. In this home, Dr. Francis Briggs served on the county draft board until he took a dose of his own prescription and became a Captain in the US Army. While her husband was away serving in an Army Hospital in New Jersey, Jenny volunteered for the most important Home Front organization of the war: the Red Cross. The Red Cross organized 20 million American volunteers to help them build wartime hospitals and stock those hospitals with everything they needed from bandages to nurses. The strength of the Red Cross was due its ability to employ the energy and enthusiasm of American women and by being one of the few organizations that offered leadership positions to women. Volunteers knit soldiers sweaters, socks, stocking caps, and bandages. Clay County organized at least 35 chapters of the Red Cross. Jenny Briggs and her fellow Suffrage Chairmen Edith Darrow Godfrey and Bessie Lewis were all members of the First Congregational Church’s Red Cross Auxiliary. Bessie Lewis’ daughter Flora was the president of the 200 member Red Cross branch at the Moorhead Normal School. American women served in countless other ways. Moorhead Suffrage chairman Esther Russell was also chairman of the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense for Clay County and led the Food Administration’s efforts to help families preserve and conserve food at home. Anna Gates had two sons who saw heavy fighting in the war. Her son Dewey was decorated for bravery for rescuing a wounded soldier from No Man’s Land and was later wounded himself. And while our Suffragists may have turned their attention toward war work, they also shamed President Woodrow Wilson for fighting for democracy in Europe while ignoring democracy at home. In 1917, Mary Darrow Weible, cousin of Moorhead’s Edith Darrow Godfrey, joined fellow Suffragists to picket in front of the White House. When the war was won, Americans looked back at the leading roles women played and the sacrifices they endured for their nation. When they asked for the vote, how could they be denied? The final passage of the 19th Amendment was the culmination of decades of work by Suffragists and the final victory was thanks to many reasons, but the fact that the amendment was sent out to the states six months after the guns fell silent and three weeks before the Treaty of Versailles was signed suggests World War I had something to do with convincing the average (male) voter that it was wrong to deny women the vote. And it wasn’t just Americans. Woman Suffragists in United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, Russia, Austria, and Hungary all won their voting rights at the end of World War I. Our next stop is the Moorhead Public Library at 118 5th St S. If you go directly across the street from the Briggs House to the brick house across 7th, you’ll see a stamp for Joseph V Godfrey in the sidewalk. The Library is two blocks west and two blocks north of here. Stop 8: 118 5th St S The Moorhead Public Library Moorhead, Fargo and many other towns in our country owe the founding of their public library to their local Woman’s Club. Sarah Comstock’s 1901 presidential address to the Moorhead Woman’s Club called for the creation of a club library, but the members’ ambition soon grew to creating a town public library. Two years later, In 1903, Moorhead attorney George Perley wrote a letter to the club calling their attention to how industrialist Andrew Carnaegie, one of the richest people in history, had recently begun a program of donating money to build public libraries. The Moorhead Woman’s Club went to work. They got a grant from Carnegie for $12,000 to build the building. They got the city of Moorhead to agree to take on the added responsibility of operating a library. They raised money to buy the city lot to build the library - the original lot was where Regal’s appliance store is today on Main Avenue and 6th Street. And once the building was built, they filled it with books. The Moorhead Public Library opened to the public in 1906. When the Woman’s Suffrage Amendment passed, Ethel McCubrey was a librarian here. She lived with her father, Grovenor McCubrey, who was the clerk of court for Clay County and would later become our state representative in St. Paul. Grovenor McCubrey was a member of the Minnesota Woman’s Suffrage Association and a member of the Men’s League for Woman Suffrage in Minnesota. Our area did a good job of electing suffrage supporting politicians from both sides of the aisle. Our State Senator Frank H. Peterson, whose house you visited on this tour, was considered a Progressive Republican. The major rival party here at that time was the Nonpartisan League, which officially endorsed Woman’s Suffrage as part of their platform. Our State Representative Solomon P. Anderson of the NPL was a member of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association. His predesessor, the future U.S. Congressman Knud Wefald, was also a Suffrage supporter. Today, the wife of Knud’s grandson, Susan Wefald of Bismarck, is the co-chair of the North Dakota Woman’s Suffrage Centennial Committee. The Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association lists two other local men as members. Both were Norwegian bachelor farmers - August Narveson and Emil Lambert. The 1916 Clay County Illustrated magazine described Lambert as “one of the progressive farmers of Moorhead township who has always been too busy to find a wife.” The state suffrage association has Lambert on a list of 11 people statewide who offered to distribute Suffrage literature. The next stop is just a block to the west on the north end of a large new brick commercial building. 115 4th Street South, the current site of Third Drop Coffee. Stop 9: 115 4th St S Formerly Burhnam Boarding House The current site of Third Drop Coffee used to be the Burnham Boarding House, home to Minnesota Suffrage Association Chairman Mae Burhnam and her mother Elsie. Mae likely would’ve been a toddler when her civil engineer father Ozro and her mother Elsie brought her to Moorhead in the early 1880s. Ozro’s brother Frank Burnham and his wife Hattie were prominent early residents of our town. Mae’s Aunt Hattie was a founding member of the Moorhead Woman’s Club and her Uncle Frank J. Burnham was a prominent attorney and the president of the First National Bank. Mae’s mother Elsie had three children but only Mae survived. Then, when Mae was about 10 or 11, her father died. After Ozro’s death, to make ends meet, Elsie Burnham ran a boarding house. Many American women, especially widowed or otherwise single women, were able to provide for their families by running a boarding house. Elsie Burnham would cook, clean, and do the laundry for her boarders. City directories indicate that there were perhaps four rooms - one for Elsie herself, one for her daughter Mae who worked as a grade school teacher, one for a longtime boarder named Lena Johnson, and the other rooms were usually men who worked as laborers and moved often. Most boarding houses provided each lodger with a bedroom and the house would also have common spaces like a kitchen, dining room and maybe a sitting room. After Elsie died, Mae took over her mother’s boarding house. The Burnham Boarding House is long gone, but it is fitting that in its place is another family business that passed down through generations of women. What used to be Moxie Java was recently renamed Third Drop Coffee as a way to celebrate the third generation of women in the family to run this business. And if you look around this block you will see so many businesses owned in whole or in part by women - Riverzen Art Studio, Joni Salon and Spa, Rustica Eatery and Tavern, Prairie Fiber Arts, across the street you might see kids playing in the back of Inspire Innovation Lab, and just a couple doors down from Third Drop Coffee, a century after people like Mae Burnham helped women gain the right to vote, we have the local office of Amy Klobachar, one of Minnesota’s two women US Senators. It’s a bit of a long trek to the next stop. Turn around and cross back to the east side of 8th Street. You’ll probably want to cross at the 8th and Main intersection, and then make your way to 204 9th St S. Stop 10: 204 9th St S The Marguerita Garrity House Marguerita Garrity was one of the Chairmen of our branch of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association. She was born Marguerita Evans and grew up on a farm outside Ottumwa, Iowa. After graduating from her rural school, she studied Domestic Sciences first at Iowa State University in Ames and then Columbia University in New York City. While there, according to family memory, Marguerita marched for Woman’s Suffrage in Washington, D.C. After graduating, “Rita” took a job teaching in Moorhead Public Schools. While dining at the Curran Boarding House she came to know a young attorney named James A. Garrity. On May 31, 1917, Marguerita and James were married back home in Iowa. The Garritys were young and ambitious but they had to try harder than most to rise through the ranks of Moorhead’s finest families - the reason for this is they were Catholic in a town where the majority of the population were Scandinavian Lutherans and the social elite had roots in Protestant New England. It’s a testament to how far we’ve come in the last 100 years that today, we find the idea of discrimination against Catholics to be absurd, but it was real back then. And the Garritys were successful. The family would eventually move to a big beautiful white house across the street from the Comstocks and two doors down from the Petersons on 8th Street, Marguerita’s husband would become Judge James Garrity, her son would also become Judge James Garrity. We already mentioned that the leading families of each American community were expected to be leaders in the war effort, and it goes the other way around, too. If you wanted to be seen as a community leader, you should be leading the war effort. Marguerita was chosen to be the head of Clay County’s Hospital Supplies Committee of the Red Cross, an extremely important post. And her husband James was very busy with home front activities, leading the Knights of Columbus’ Liberty Loan drive and giving patriotic speeches at theaters, picnics, or wherever people might need a jolt of war fever. Marguerita Evans Garrity served as Suffrage chairman at the same time as Anna Gates, Esther Russell and Ann Kossick. She likely struck up a friendship with fellow Catholic Ann Kossick, and soon they were family. In 1919, Anne Kossick married Marguerita’s brother and moved to the farm in Iowa. The 1920 census shows that two of Anne’s sisters, Helen and Clara Kossick, were living here in the Garrity home as boarders. Anne Kossick Evans proves that Suffragists as individuals defy stereotypes. The Kossicks were a large German Catholic immigrant railroad family, and they were NOT Temperance advocates. Her brother Leo Kossick gained local fame as an amateur boxer and later ran pool halls, taverns, and bowling alleys. Her brother Alex was a bartender at the Blackhawk Café until he opened Kossick’s Liquors, and Anna’s Iowa farmer husband, Marguerita Garrity’s brother, was no Dry either. And while I’m not sure if Marguerita was as alcohol-friendly as her name implies, we know her husband liked liquor. As County Attorney, James Garrity was the most important figure in legally ending Clay County’s 22 year long experiment with Prohibition. One final stop. If you’re facing the front door of the Garrity House, turn to your right and walk south down 9th Street. On the other side of the parking lot of the Townsite Center, which used to be the old Moorhead High School, you’ll see a big blue two-story house. We are going to a big yellow house just on the other side of that. You can follow the sidewalk around the block or you can take a shortcut through the parking lot to 421 9th St S. Stop 11: 421 9th St S The Sharp House If any family could challenge the Comstocks for the title of Moorhead’s most respected founding family, it would be their good friends James and Philadelphia Sharp, who lived in this house. James Sharp, like Solomon Comstock, was also here for Moorhead’s rough, Wild West birth. He rose to become Justice of the Peace and the founder of our school system. That large building behind you that is now Sharp View Apartments used to be a school named for the Sharp family. James and Philadelphia Sharp’s children became prominent leaders of our town’s second generation. Their daughter Philadelphia Sharp Carpenter inherited her parents house, and in this house, in 1930, a meeting was held to establish a local chapter of the League of Women Voters. The League of Women Voters is the direct descendant of America’s Woman’s Suffrage organizations. The League was born in 1920 because, after generations of struggle and organizing, the National Woman Suffrage Association had no reason for being anymore. They won the vote! So in their victory, they disbanded, and reformed as a new organization devoted to voter education they called the League of Women Voters. Just like before, local chapters formed throughout the country. The chapter of the League formed in this house in 1930 was not Moorhead’s first chapter - we had one right away in 1920. Our first chairman was Lucy Sheffield, a music teacher whose father was a railroad laborer. Other officers included Marie Thompson (a young daughter of a farming family who was a WWI Red Cross leader), Nora Dickerson (whose husband was the new president of Moorhead Normal School) and Edna Stadum (wife of a Glyndon banker). Today, the League of Women Voters of the Red River Valley, headquartered in Fargo-Moorhead, serves voters on both sides of the river. This nonpartisan group holds local candidate debates, they have a lunch-time lecture series where polacy leaders or scholars talk about important issues of the day, and they encourage people to vote and be active participants in our democracy. Membership is open to both women and men, and the work of the League of Women Voters of the Red River Valley benefits every one of us in the community. If this sounds like something you like, check them out. Well, that’s our last stop. The Comstock House where we began this walk is just a block ahead and a block to the right. I’d like to thank you for coming along on this walk to remember some people who worked to wake up our nation to the self-evident truth that all of us are created equal. Don’t take for granted what they fought so hard to give us…your country needs active and informed citizens. You have a duty, and a right, to Vote. Extending the Home: Women's Clubs Work for the Vote Dr. Ann Braaten August 17, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * NDSU professor Dr. Ann Braaten delivers a lecture commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. "Extending the Home" Women's Clubs Work for the Vote" offers a broad overview of the women's suffrage movement in the United States before focusing on the efforts of suffragist Kate Selby Wilder in Fargo, North Dakota. This lecture was recorded and webcast live via Zoom and Facebook on August 12, 2020. Please join us on Facebook, sign up for our eNewsletter, and check out our Events Schedule to watch future webcasts from the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. Recorded lectures will be archived on the HCSCC Blog and YouTube. Birdsfoot Trefoil Mark Peihl July 16, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * Every year around this time, a low growing plant with lovely golden-yellow flowers covers the boulevards along Moorhead’s streets. You’ve probably seen it. The plant forms a thick mat, often draping gracefully over the curb and onto the street. It’s called Birdsfoot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), a species introduced to provide forage for livestock. In the 1950s, it briefly became a specialty crop, raised for its seeds — and Clay County was a leader in its production. Birdsfoot Trefoil forms multiple inch-long seed pods radiating from the tips of its stalks. Some people think this looks like a bird’s foot. The Trefoil part of its name comes from the three leaflets on each leaf. It is a remarkably adaptable plant that is native to most of Europe, much of Asia and north Africa. One theory suggests that its initial US introduction could have come from ship ballast dumped along the Atlantic coast and the Hudson River. By the early 1930s, it was firmly established in two locations, western Oregon and eastern New York state. In the early 1930s, a New York Soil Conservation Service agronomist recognized its potential value as livestock feed. He arranged for boys enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps to hand harvest wild seeds and had them planted in test plots. Birdsfoot Trefoil is a legume. Like alfalfa and clover, it captures nitrogen from the air and fixes it in the soil, fertilizing it. Tests showed that Birdsfoot Trefoil provided good forage, could be grown on poorly drained and alkaline soils ill-suited to alfalfa and, unlike clover, did not cause a fatal digestive disease in livestock called bloat. Seeds from New York and imported from Europe were sent to test facilities around the country. In 1938, a test plot in Winona proved it could be grown in Minnesota. In 1941, newly hired Clay County Agricultural Extension Agent G. E. May began a successful program to get farmers to improve the quality of their pastures. The drought of the 1930s left many pastures in rough shape. May encouraged farmers to plow up their grasslands and replant with mixtures of grass and legumes. In 1948, a handful of Clay County farmers began planting regular test plots and incorporating Birdsfoot into their mixes. The mix did well, once it was established. By 1950, there was a run on BIrdsfoot seed. Ag Agent May, in his 1950 Annual Report wrote, “About a year ago, Birdsfoot Trefoil was mentioned at every opportunity in discussing pastures. When it was learned the seed source was very limited and that it was extremely high priced, everyone’s mouth began to water, they wanted some seed. They have had several doses of ‘you can’t have it yet but wait.’” Farmers in Norman County began raising Birdsfoot for seed. In 1955, they formed the Red River Valley Certified Trefoil Seed Growers Association to promote its production and establish standards for certified seed. That year, Herman Lee of Felton planted forty acres. Art and Hank Skolness of Glyndon put in several hundred. Neil Peters of Moorhead later put in eighty. As a new crop, it came with a steep learning curve. The NDAC Extension Service published a how-to circular on raising Birdsfoot but it proved to be a finicky crop to produce. It required chemical weed control to get established and if harvested when it was too dry, the seed pods popped open, spilling the seeds prematurely. Herman Lee harvested his first crop in 1956 when the seeds had a fairly high moisture content. He managed to get a respectable 625 pounds per acre. Certified seed sold for $2.00 per pound in Fargo that year. He spread the seeds out on the floor of a Quonset building to dry but they over heated and much of his crop did not match the Association’s germination standard. In a wet year like 1958, Birdsfoot produces a lot of foliage. It can take a long time for it to dry enough to cut properly. But by then, the pods are too dry and they pop. Neil Peters tried to make the harvest easier by spraying a defoliant on the crop. The top leaves dropped off but the seed pods popped, too. Peters lost 2/3 of his crop. The Skolness brothers had better luck. In 1957, they told new Clay County Ag Extension Agent Ozzie Dahlenbach they expected to harvest six to seven thousand pounds of the Viking variety and twenty-five to thirty-thousand pounds of the Empire strain. Empire is a low growing cultivar best suited for grazing. Viking is a taller standing variety better for cutting as hay. Dahlenbach reported that the brothers “have put in a complete processing unit which will take care of practically all the cleaning jobs that one might run into in processing the seed.” Despite the problems, in 1958, Clay County farmers raised 85% of the seed submitted for certification testing in Minnesota. But by 1959, the price of Birdsfoot Trefoil dropped by half. Though farmers continued to use it in their pastures, production for seed disappeared. After 1960, Extension Agent Dahlenbach never bothered to report BIrdsfoot Trefoil as a specialty crop in Clay County. Today, Birdsfoot Trefoil is found in nearly every Minnesota county. It spreads easily and is difficult to eradicate. It’s especially problematic in virgin or restored prairie environments where its dense mat chokes out native species. The Minnesota Department of Agriculture has assessed Birdsfoot through its noxious weed regulation evaluation process and recommended that it “not be regulated to continue to allow its use in agronomic grazing systems.” However, it recommended “that people do not intentionally seed Birdsfoot Trefoil in fields adjacent to native prairie management areas and do not include Birdsfoot Trefoil in wildlife or deer seed mixes.” U of M Extension Ag Educator for Clay County, Randy Nelson told me he did not know of anyone in the county intentionally growing Birdsfoot, though there may be some out there. Various cultivars are available from regional seed houses. Though it’s probably not a good idea to plant it in your yard, there are no rules against enjoying Birdsfoot Trefoil’s lovely flowers where they are. Invasive or not, they are a sure sign of early summer in Clay County. Volunteers of a Different Kind: Clay County on the Canadian Front of WWI Mark Peihl June 25, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * When the U.S. entered World War 1 in April 1917, the country was swept up in a surge of volunteerism. Even here in the isolationist Midwest, thousands of young Americans lined up to assist the nation and our European allies in a variety of ways. In addition to the two million men who enlisted for military service, many women stepped up. In Clay County, they included Rose Clark from Barnesville who became a Red Cross nurse. She served in a forward hospital under fire near the front line. Francis Lamb from Moorhead was a canteen worker for the YMCA in France. Signe Lee from Moland Township signed on as a US Army nurse. Elizabeth McGregor from Hawley worked as the director of a group of nine small hospitals attending to the needs of civilians for the American Fund for French Wounded. Their stories are told in our current exhibition War, Flu & Fear: World War I and Clay County. The war had raged in Europe for nearly three years before America entered the fray. American volunteers famously served as ambulance drivers in France and Italy, including future literary luminaries John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway. Some young Americans couldn’t wait to get into the fight and enlisted in the French, Canadian, or British armed forces. American aviators formed the famous Lafayette Escadrille in 1916. We’ve identified at least twenty Clay County natives who joined foreign service. The vast majority were like Bruce Awrey. He grew up in Hawley and served a year in the Minnesota National Guard, but moved to Canada as a young man, took Canadian citizenship, and a job in Alberta. He enlisted in the Canadian Army in May 1916 and spent the war driving trains in France. Other Clay County natives went north before the war to take advantage of the Canadian version of the Homestead Act. We have found, however, two Clay County men who joined the Canadian Army as US citizens. At least apparently. George Oliver Burnette claimed he was born in Glyndon in 1890 and that in December 1915, he was working in a Glyndon butcher shop. That month in Winnipeg, he signed his “Attestation Papers” (Canadian enlistment papers) in the 144th Battalion, Winnipeg Rifles. He apparently had a change of heart and on August 6, 1916, he went AWOL from Camp Hughes, Manitoba. A month later he was declared a deserter and was never seen again. It is curious that we could not find any evidence that he ever lived in Glyndon. Men went north for all sorts of reasons. He may have pulled the Glyndon identification story out of his hat. The other is at least more straightforward. Arthur Alfred Buresson was the youngest of Nils and Inga Buresson’s six kids. The Norwegian immigrants moved from Illinois (where Fred, as he was known locally, was born in 1894) to a farm in Cromwell Township in 1901. In 1917, Fred tried to join the US Army but was rejected because he stuttered. In December, Fred went to a recruitment center in Minneapolis and started the Canadian enlistment process. He traveled to Montreal where doctors pronounced him fit for service despite his stutter. He fibbed a bit on his attestation papers, claiming he was born in Winnipeg. He gave his first name as “Arthur A.” and spelled his last name Bursson. He claimed that his civilian jobs were “quarryman” and “navvy.” I don’t know any quarries in Clay County where he may have worked. A navvy is a British term for someone who builds roads, canals and other transportation infrastructure. He was inducted into the Internal Waters and Docks Service, part of the Royal Engineers. This was an odd and important part of the Canadian-British military. The IWD was responsible for the orderly shipment of war material from Britain, across the English Channel to France, and then onto where it was needed at the front. Much of this stuff was shipped over canal systems, hence the name. The Brits built a huge shipping base at Richborough on the east coast of Kent in England. Fred was sent there in early 1918 for training. His movements are somewhat sketchy after that. According to his service record, on March 26, he was transferred to an Inland Waters and Transportation unit in France. We know he was disciplined there in July 1918 for being “improperly dressed” in town and docked three days’ pay. The IWT soldiers rarely made to the front but at some point, Fred was injured by poison gas. We don’t know when he was hurt but he was hospitalized in December, 1918 - after the Armistice. In February, 1919, Fred was loaded onto the HMS Halifax for the trip home. He died at sea on March 8, from “after effects of gas poisoning.” The Canadians sent his body home to Clay County. He’s buried with a British military headstone in the Hawley Cemetery. B.C. Sherman's Fly Net Lisa Vedaa June 15, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * We don't see these much anymore, but our recent blog about the 1872 horse influenza epizootic reminded me of all of the wonderful horse artifacts in our collection — including this horse flynet donated by B. C. Sherman, a long-time Moorhead harness maker. The fly net is made of strips of leather tied into a net to spread across the back of a horse to provide enough movement while a horse is working to keep horse flies from landing and biting. Bion C. Sherman came to Moorhead from Michigan in the 1880s. After some farm labor and lumbering in the Minnesota woods for a winter, he returned to Moorhead and worked for harness maker R. M. Johnson at his shop on Center Avenue near 6th Street. Sherman purchased his own shop a few years later and operated there until the age of 82 in 1938, when the building was torn down. This fly net and some harness pieces were donated to the Historical Society in 1938 — probably as Sherman was moving out of the building, which served as both his shop and home. Sherman became a resident of the St. Ansgar Old People’s Home before he died in 1947 at the age of 90.

COVID Victory Gardens

Markus Krueger May 12, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * Reports are coming in from parts of the country where spring planting comes sooner than here: Covid-19 is causing an outbreak of vegetable garden fever. Growing your own food makes a lot of sense at a time when a trip to the grocery store has an element of risk, when our food supply chain is warning of disruptions, and when people have a lot of extra time on their hands. Growing vegetable gardens during a time of crisis is bound to remind people of the most successful home gardening campaign in our nation’s history: the Victory Gardens of the World War II. While everybody has heard of Victory Gardens, the idea of the homefront war garden actually began with World War I Liberty Gardens. National War Garden Commission president Charles Lathrop Pack explained Liberty Gardens would “arouse the patriots of America to the importance of putting all idle land to work, to teach them how to do it, and to educate them to conserve by canning and drying all food they could not use while fresh. The idea of the ‘city farmer’ came into being.” That may be a bit of an overstatement. People in cities certainly did grow vegetable gardens before 1917, but the Liberty Gardens of WWI really produced results both here and nation-wide. The new Clay County Extension Agency helped 300 people in the county start a garden and taught 500 local women to can. These women canned 10,000 quarts and dried 5 tons of fruits and veggies. Americans canned 1.45 billion quarts of food in 1918. Liberty Gardens also had a major effect on the development of community gardening in America, as urban residents without yards of their own shared resources, tools, and labor to cultivate large lots together. Gangs of gardeners even bullied owners of vacant lots to let them turn the “slacker land” into a garden. No such tactics were needed in Moorhead, though. Susan Lally offered 17 lots she owned just north of the courthouse to anyone looking for free gardening space. Students were encouraged to grow a school garden, and the kids at Glyndon Elementary did just that. A generation later a Second World War called gardeners into service once more and on a greater scale. It is estimated that 1 in 3 vegetables grown in America in 1943 were grown in a home or community Victory Garden. According to county extension records, an astonishing one in nine residents of Clay County attended classes on food preservation in 1944. Those who attended classes canned 730,714 quarts and dried 455,094 pounds of fruits and veggies just in this county! And for those who needed gardening space, “The Merchants and Professional Men of Moorhead” sponsored a community garden by the courthouse and Barnesville offered free land by the fairgrounds. I will warn you, however, that once a new gardener realizes just how delicious homegrown tomatoes are, they will find that, like the flu, vegetable garden fever returns every year. *This article is taken from Clay County Histories, an HCSCC column published in the FM Extra. |

Visit Us

|

Resources

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed