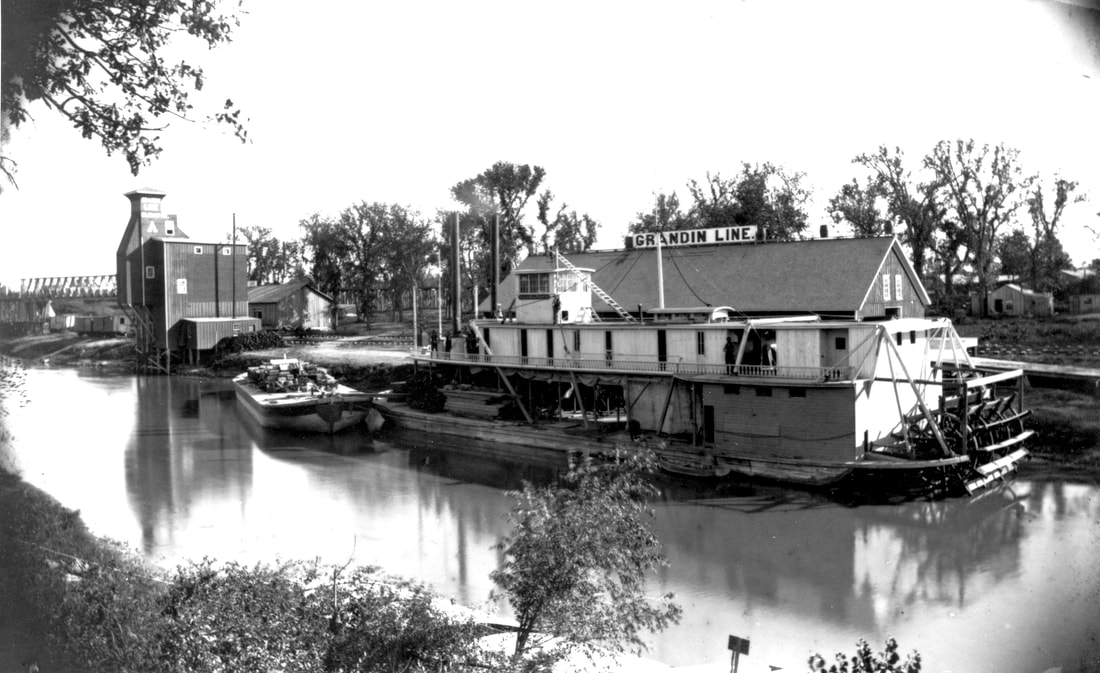

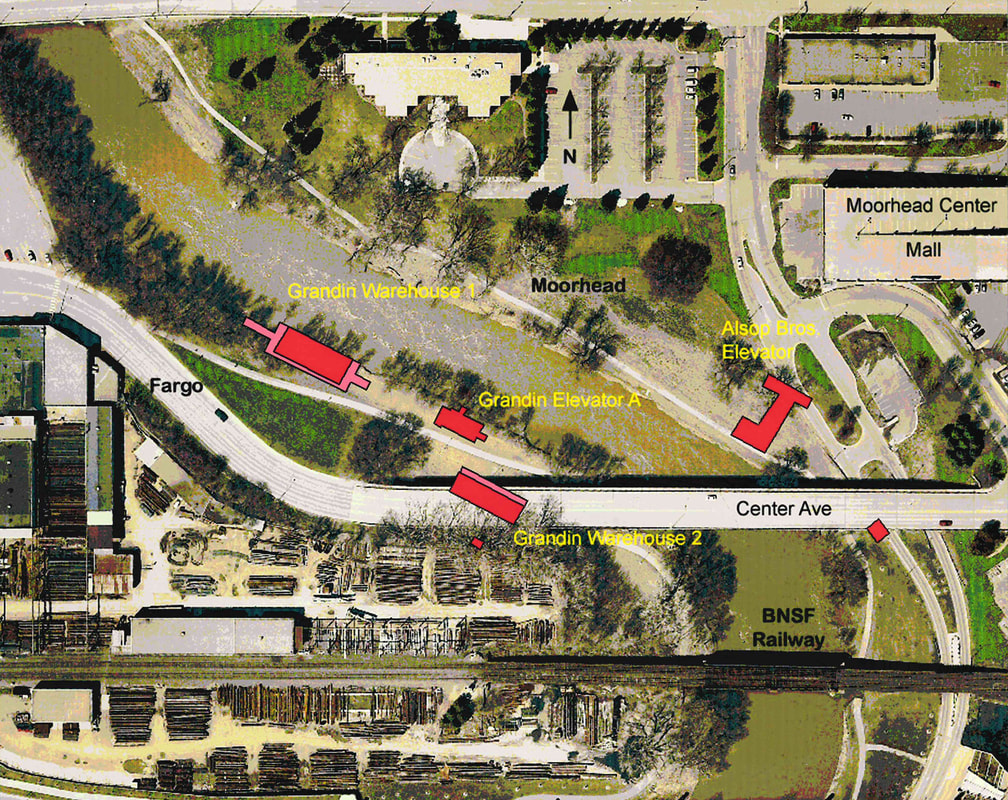

Alsop Brothers’ Steamboats at Moorhead, 1881. Piles of lumber from the Alsops’ mill await loading onto their barge, Aimee, and steamboats Pluck, at right, and the H. W. Alsop, at left. This is the only photo we have of the H. W. Alsop, the finest boat to ever ply the Red. She boasted the best passenger accommodations of any local steamer. On her third trip sparks from her smokestacks caused a devastating fire. Though rebuilt, she was never the same. After the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway bought the Alsops’ boats in 1884, she was sent to Grand Forks where she worked for several years. The Pluck remained in Moorhead until 1888 (HCSCC). Fargo-Moorhead Steamboat Landings, 1880s Mark Peihl May 4, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * In the 1870s and 1880s steamboats plying the Red River tied up just two blocks south of today’s Hjemkomst Center. The waterfront was located between today’s Center Avenue and 1st Avenue North bridges. It was a very busy place 130 years ago. Initially, in the 1860s, steamers hauled furs from Canada to Georgetown, thirteen miles north of Moorhead, where they were transferred to Red River ox carts destined for St. Paul. Trade goods went north along the same route. Railroads reached the Red River in 1871 and Fargo-Moorhead popped up. The faster and more efficient trains put the carts out of business but gave steamboats a boost. Lots more stuff was shipped to and from Canada. In 1878 rails reached Winnipeg. Like the carts before them, it looked as if the boats would disappear, too. But steamboat owners took on a new task, carrying farmers’ wheat from isolated riverside grain storage elevators to rail heads like Fargo and Moorhead. From 1878 to 1888 steamboats carried wheat to facilities on both the Fargo and Moorhead riverbanks. The accompanying illustrations are from this period. The Grandin Steamboat Line shipped wheat from the Grandin brothers’ huge bonanza farm near Halstad, Minnesota to their elevator on the Fargo bank. They had one boat, the J. L. Grandin. On the Moorhead side, brothers Charles and Henry Alsop built facilities for loading wheat and milling lumber. They had two steamboats, the side-wheeler Pluck and the H. W. Alsop, the finest boat to ever ply the Red.  Grandin Line’s Operations, about 1880. The J. L. Grandin waits on the Fargo side of the Red to be loaded with lumber and shingles for a return trip north. The 120-foot long sternwheeler also carried passengers. The narrow doorways on the second deck lead to very basic cabins. The sternwheeler is tied up alongside the Grandin’s Warehouse Number 1. Their Elevator A and Warehouse Number 2 can be seen at left (HCSCC). Both companies struggled for a few years but eventually the railroads won out. In 1883 the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway built a branch north from Moorhead along the Red to Halstad. The next year the St. P., M & M Railway bought the Alsops’ two steamboats. The railroad continued to ship through the Fargo-Moorhead facilities for a few years but with the completion of a railroad line south of Moorhead to Wolverton in fall 1887, the end was near. In May 1888, the former Alsop boats left Fargo-Moorhead for Grand Forks and the Grandins permanently docked the J. L. Grandin. Local steam boating came to an end.  The Fargo-Moorhead waterfront today. The red shapes show the locations and footprints of the two companies’ buildings in 1884 on a modern aerial photograph. On the Fargo side are the Grandin Steamboat Line’s Elevator A, and Warehouses 1 and 2. On the Moorhead side the Alsop Brothers’ grain elevator is shown. Railroad spur lines ran down to both operations from the Northern Pacific Railway (now Burlington Northern Santa Fe) tracks, visible at the bottom of the photo. The small squares mark storage buildings (HCSCC).

1 Comment

The Horse Flu of 1872 Comes to Clay County, Minnesota

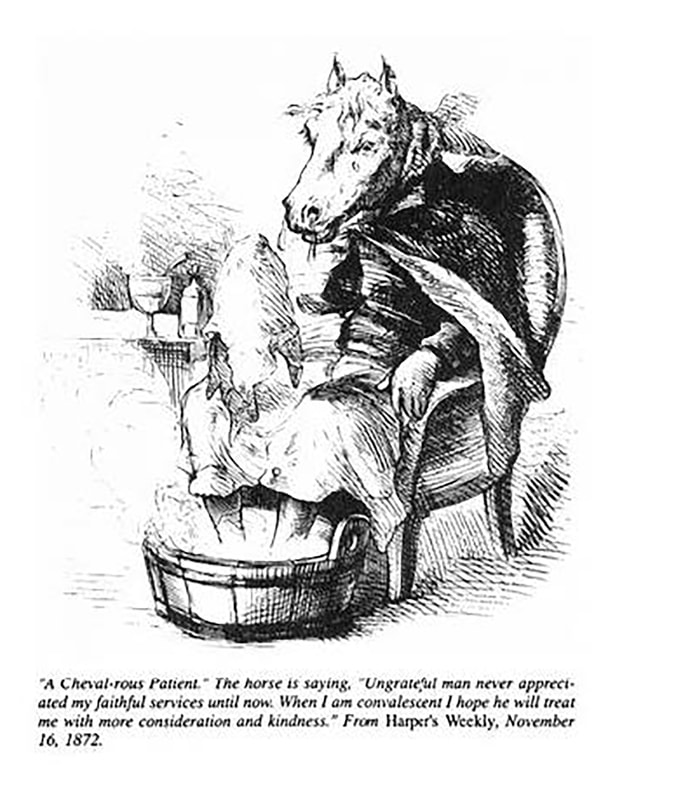

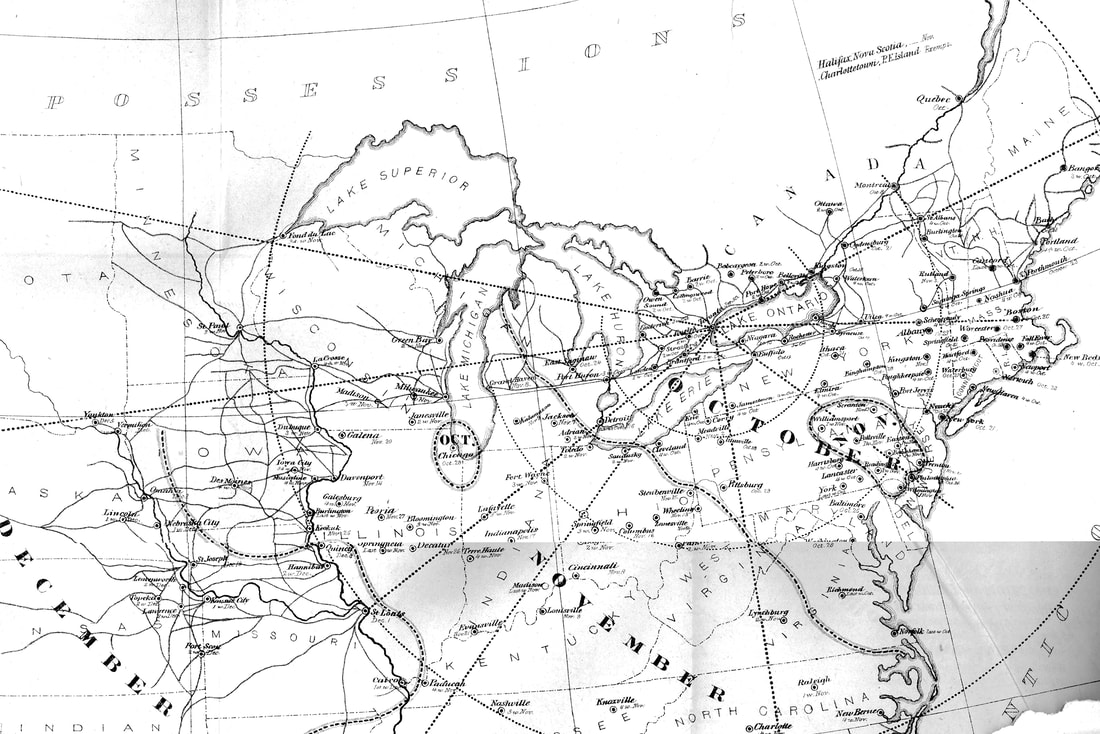

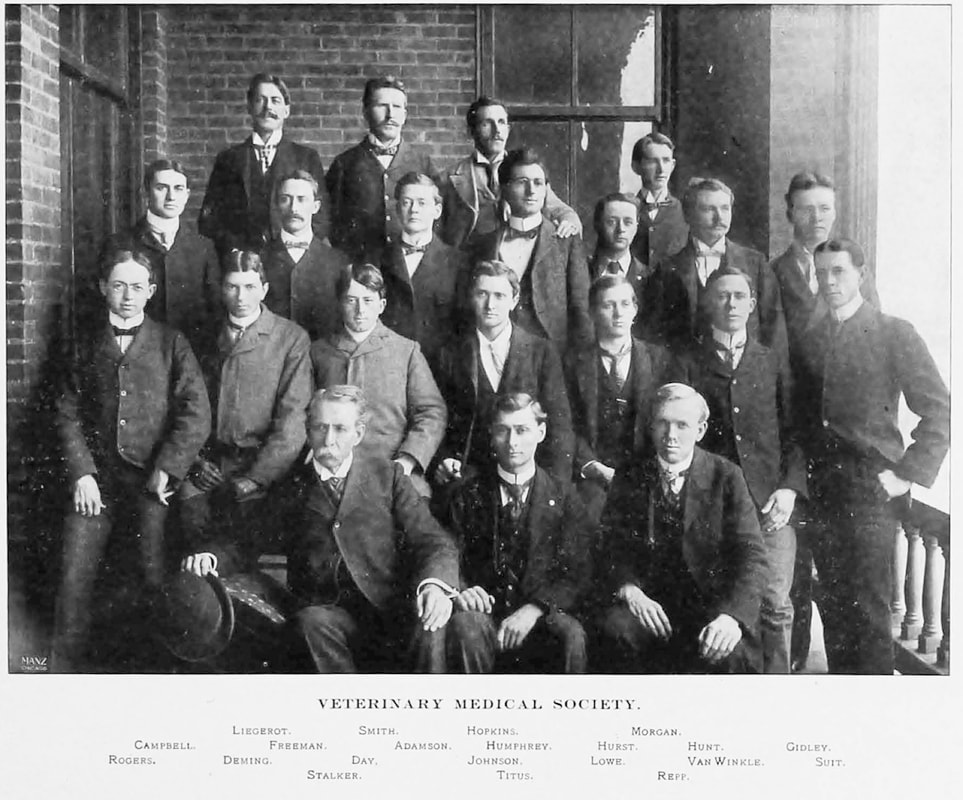

Davin Wait April 22, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * Life in the early years of Clay County, Minnesota, was far more dangerous than it is today. Tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and cholera confronted the limitations of public health, sanitation, and science in the 19th century. From 1872 to 1900, that spelled out a life expectancy of roughly 48 years and cemeteries where half of the community’s graves belonged to children 12 years old and younger. A quarter of them belonged to children younger than 12 months. It meant that Clay County families in the 19th century faced an infant mortality rate of 160.4 (number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births — the global high today is Afghanistan's 110.6). And if we look to the destruction of Native American populations that coincided with the expansion of Europe and the United States into the Americas — an estimated 90% population loss from pre-Columbian levels that reached its nadir in 1900 — we see an even more sobering look. However, the first true epidemic in Clay County’s history wasn’t really even an epidemic at all. It was a novel flu virus that local residents suffered only indirectly. It was the Great Epizootic, otherwise known as the Horse Flu of 1872, and it effectively ground America’s local, horse-driven economies to a halt. Horses experience influenza much like humans, so the Great Epizootic brought symptoms including runny nose and eyes, cough, fever, weakness, and chills to nearly all of the horses, donkeys, and mules in North America. The disease was first identified near Toronto at the end of September in 1872. Professor Andrew Smith of the Ontario Veterinary College believed the disease originated among pastured horses fifteen miles north of the city. By Friday, October 4, nearly all of the horses in Toronto’s streetcar and livery stables were sick. Two and a half weeks later it reached Boston and New York City. On Thursday, October 24, it was in Chicago. By the end of November, it was reported in St. Paul, Des Moines, New Orleans, Atlanta, and most of the cities between. An ill-timed shipment of horses destined for Governor Francisco Ceballos y Vargas brought the disease to Cuba. The isolation and landscape of Nicaragua finally stopped it just short of South America in September of 1873, an entire year after it had popped up in the Canadian countryside. In an 1874 report issued to the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Cornell veterinarian Dr. James Law estimated that 80-99% of horses, mules, and donkeys in North America had been struck by the disease. Roughly 1-2% of them died, with some urban areas reporting equine mortality up to 10%. It touched down in the Red River Valley in December, 1872, where it was first reported by Glyndon’s Red River Gazette the day after Christmas: The horse disease has finally reached this place and Moorhead. So many of the stage horses on the line between Fort Garry and Breckenridge are sick, that the stages between Moorhead and Breckenridge have been taken off entirely, and from Moorhead to Fort Garry fiery untamed oxen careen over the prairie with the mail at the rate of a mile and half an hour. The McDonald brothers, of Glyndon, started last Tuesday from Moorhead with five teams loaded with tea for Fort Garry, but their teams were taken sick on the road, and after getting as far as Frog Point, they were compelled to give up the trip, and put their horses under treatment. One of the brothers remained to take care of the teams, and the other two took Foot and Walker’s line back to Glyndon. The only case of epizootic we have heard of yet in Glyndon is that of one of Hendrick’s ponies, which now exhibits all the symptoms, but in a mild form. While recent research from Dr. Michael Worobey at Arizona State University has connected the Great Epizootic of 1872 to the novel H1N1 strain of influenza that wreaked havoc around the globe during World War I, in its own time the disease was primarily an economic and technological disaster. Though much of the United States had already adopted steam engines, railroads, and telegraphs, draft animals like horses and mules were still vital to the American economy. Agriculture, transportation, and communication very much depended on the health of these animals. When the flu struck, local economies ground to a standstill for weeks at a time as laborers confronted the inadequacies of human power compared to horsepower. One of the most striking examples of this occurred in Boston, where a massive, two-day fire beginning on November 9 took shape in the absence of the horsepower necessary to pull the fire departments’ engines. Louis Sullivan, a student at MIT at the time of the fire, recalled a fire engine arriving too late to a burning warehouse: "The people at curbside waited, but still no firemen came. Fire engulfed the warehouse, then its roof and floors collapsed. Finally a fire engine arrived, too late. Men, not horses, pulled the apparatus." The city lost 776 buildings over 65 acres of land and nearly $75 million in property value. As epidemics (or epizootics) often do, the devastation of the Horse Flu of 1872 prompted a revitalized effort toward social and technological innovation. Here on the edge of the frontier, railroads and settlement immediately changed the landscape and ecology. Innovation in healthcare and medicine came, as well, it just moved a little slower. * * * * * * Want to learn more about the Horse Flu of 1872 in Clay County? Become an HCSCC member and dig into our Summer 2020 newsletter! Join HCSCC Programming Director Markus Krueger for a brief video tour of HCSCC's local exhibition, "War, Flu, & Fear: World War I and Clay County." The exhibition explores Clay County's experiences during a time marked by global war, disease, and paranoia. It's a sobering look at perhaps Clay County's darkest hour, but brighter and better years followed. Walter and Karin Krueger in the 1952-53 Polio Epidemic

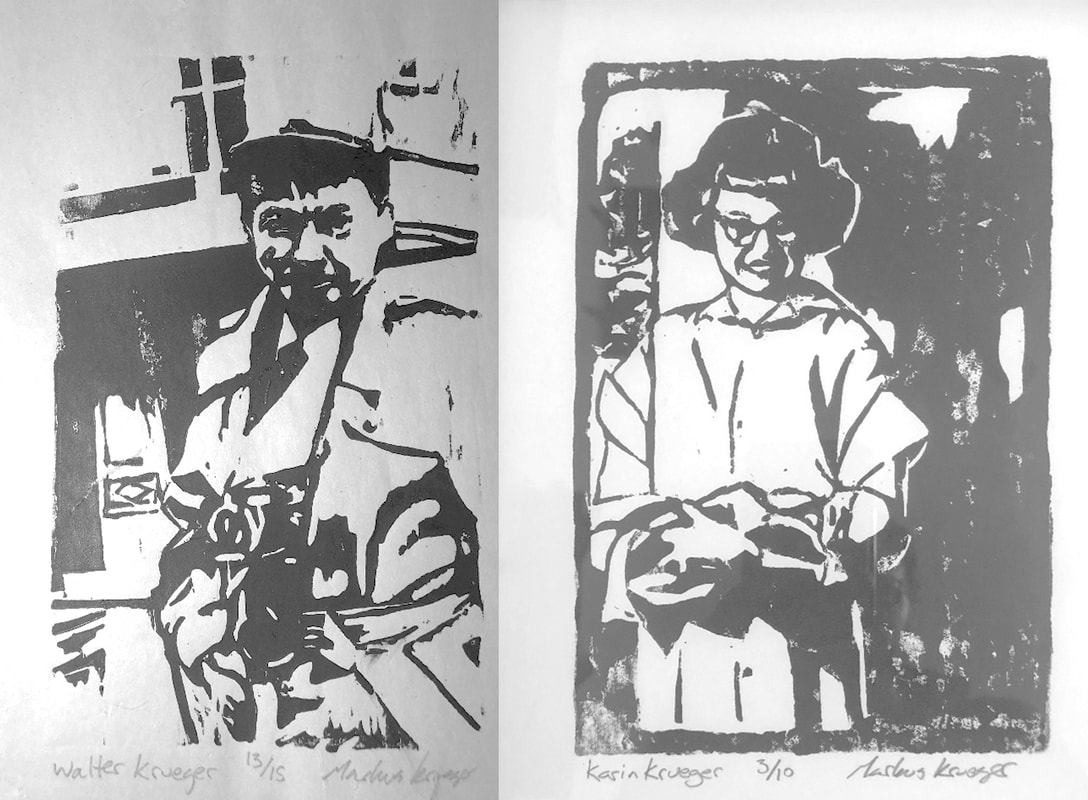

Markus Krueger March 26, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * I remember when I was not yet ten, my grandpa and grandma, Walter and Karin Krueger, wrote up their life stories. They kept working on it until grandpa’s was 80 pages and grandma’s was 122. Everyone take note: this is the best possible gift anyone can give to their loved ones. As I read the pages, in their words, I remember their stories and I hear their voices. My feisty grandma Karin had the Scandinavian accent so often imitated when poking fun at Minnesotans. Walter’s voice cannot be imitated. In 1952, polio deadened his speaking muscles. In time, he trained different muscles in his throat to move and contract and vibrate with the breath he could muster from the quarter of a lung that still functioned. His voice was raspy, deep, kind of (but not exactly) like what you hear coming out of an old fast foot drive-thru intercom. You and I cannot make the same noises. He was athletic as a young man growing up in Fargo. Not after 1952. Actually, I take that back. Every little thing he did required athleticism. Polio deadened his leg muscles, so he learned to walk by locking his legs straight and propelling himself forward using some still-living ankle muscles on the tops of his feet. All of his children and grandchildren associate him with his crutches. They were with him always, almost extensions of himself. He could not move without them and yet he could practically juggle with them. Years after his death, as several of his descendants were talking about how we have his crutches or pieces of them as mementos of him, my dad pointed out how much his father hated his crutches. But what Walt Krueger saw as a symbol of his disability, those who knew him saw as symbols of his adaptability and tenacity. Or maybe we just like them because they remind us of him. Heck, he’s probably the reason I wear so much plaid. He was a quiet man, perhaps since talking could be difficult for him and those who did not know him could often not understand him. We listened carefully when he spoke because if he chose to say it, it must be worth listening to. That, and what he said was usually smart – he was, after all, an industrial chemist for 3M responsible for inventions like the reflective lettering you see on highway signs and, also, the tape on disposable diapers. But as I get older, what I admire most about Walt Krueger is his patience. And the reason I admire him for his patience is because he was not by nature a patient man. In fact, I think he spent much of his life frustrated, irritated and exasperated. Frustrated that the McDonald’s drive-thru guy can’t understand his order. Irritated that he’s trying not to get toppled over by his grandkids who are running around like crazy people. Exasperated that he wants to go inside a building but the steps leading to the door each look ten feet tall. Patience was forced upon him. He could not scream out, or jump up and down in a tantrum, or physically overpower a misbehaving kid, or go for a run to let off some steam. He handled obstacle after obstacle quietly, persistently, using his engineer’s mind to adapt the world to himself and retraining his body to do tasks that everyone else takes for granted…or, as I often saw him deal with obstacles, scowl, roll his eyes, and hrumph as if saying to himself “let it go. It’s not worth the effort.” When I feel impatient, I look to Walt Krueger’s example for strength. The following paragraphs are excerpts from the unpublished memoirs of Karin and Walter Krueger describing the Polio Epidemic of 1952-53. Walter Krueger: When I had been at 3M for a year I went for a vacation to Wisconsin. Karin’s Aunt Evelyn Bonin and family were at Antigo and we stayed with them for a few days. We stopped at Duluth on the way home and left Ray [their young son] with Karin’s folks. We came home to St. Paul and went to visit the Walker Art Center. We were going to go back to Duluth on Sunday to retrieve Ray and settle back into our routine. It was not to be. I awoke Sunday morning feeling queasy and wondered if it was something I’d eaten the previous evening. I went to bring in the paper and found it difficult to coordinate. I felt a growing panic as I realized something was wrong. I called Dr. Sekhon and was distressed to find my voice didn’t work very well. I awakened Karin and she tried to arrange transportation to Anchor Hospital. I vaguely remember stumbling into Anchor Hospital supported by Karin and our neighbor, John Dowdall. Neither cabs, ambulance or police would handle such a high risk passenger as a suspected polio patient. It had much the same respect, or even greater, than the fear now associated with AIDS. [note: this was written at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1990.] I remember lying on the gurney awaiting the outcome of the analysis of the spinal tap. It is impossible for me to separate real memory from hallucinations for the days or even weeks that followed. 1952-3 was the last epidemic year for polio due to the development of effective serums for immunization. That year the patient load was heavy and staffs were strained to the breaking point trying to cope. Karin was there all day every day serving as a private nurse to supplement the overworked staff. My condition deteriorated to the point that it was recommended that I be put in an “iron lung.” I felt that going into the lung was a one way trip so for the sake of my morale they elected to delay that move for as long as possible. I did manage to escape that. I was unable to swallow and was fed through a tube down my nose. Speech was virtually unintelligible. Leg movement was gone and my arms were too weak to hold up a comic book. Hot pack sessions and exercise therapy became the highlights of the day. Eating was the goal to achieve to graduate from Anchor to Sheltering Arms where convalescent therapy would begin. The head doctor was a pompous politician with a bright, irrelevant remark for everyone. His two assistants were both hard working young doctors but one was all business and as impersonal as a rock. The other was as compassionate as he was conscientious; a literal lifesaver. Eventually I did arrive at Sheltering Arms. A nurse named “Donney” took care of our ward; she reminded me very much of my Aunt Alma. Dr. Wallace Cole was a distinguished gentleman with a lot of empathy for his patients. As strength came back to my arms I started to relearn to walk. This was a precarious adventure on legs that would lock but otherwise had little response. Just getting up from a wheel chair was a gymnastic feat of no mean proportion. For a time I envied a fellow whose legs worked great but whose arms and hands were useless. I soon grew to appreciate that getting there was no use if you couldn’t do anything when you got there. I was sustained all through this trial by Karin’s faithful daily appearance and support. I was determined to resume my career and support my family. The suspicion that I might never regain the use of my legs or swallow was slow to dawn and emotional adjustment came gradually. I took Karin’s presence for granted without regard for the effort and sacrifice she made in riding a chain of busses across town twice a day. Her dad brought Ray to St. Paul and he baby sat all day while Karin was with me. I was allowed to go home for a few days at Christmas time. I was down to 110 pounds and looked like a Belsen or Auschwitz survivor. I came down with Pneumonia and only Dr. Sekhon’s valiant effort got me into Bethesda Hospital instead of being returned to Anchor. The battle to breath was to become a regular event for several years. At least once each spring and fall I’d catch a cold that often turned into pneumonia. I pleaded to remain at home for these bouts because the regimen at the hospital wasn’t in synch with my needs. Good intentioned dieticians never seemed able to understand the difference between chewing and swallowing. I couldn’t make them believe that hamburger and mashed potatoes were among the hardest things to swallow. Again Dr. Sekhon cooperated but he always worried that I might need special equipment only available at the hospital. I started back to work half days but it was the coming and going that was the most difficult. Soon I was going full time. MY coworkers were very supportive. When I was just beginning to recover they took up a collection for me at the lab that gave us a savings account of $700.00. I have always been grateful to 3M they took back this person with one year’s service and hardly able to walk. Many of my ward mates at the hospital were facing trying to start new careers because their old jobs were now beyond their abilities. Karin Emberg Krueger: Sunday morning Walt got up to get the paper and discovered he was very weak and dizzy. He went to bed while I called Dr. Sekhon. He told me to get Walt to Anchor Hospital. When I mentioned polio neither cabs nor police would come near us. So I ran to the neighbors and found most of them were at church. Clarence Etter backed away from me in horror; Carol Anne was about due and he was afraid. John Dowdall was in the back yard and when he learned of the problem immediately offered his help -dear, dear man! Between us we dragged Walt to John's car and we went to Anchor. The whole afternoon passed before we got the diagnosis of polio confirmed. I signed two papers; one for a tracheotomy and the other for an Iron Lung. Then they sent me home with John. At dawn the next morning I got a call to come as quickly as I could because Walt was dying. The cab came so soon I was buttoning skirt and blouse as I ran down the stairs to the cab. We sped to the hospital only to be told that the immediate crisis was past. After a short 20 minutes with him they sent me home again under a two-week quarantine. A week later Walt had another crisis - he'd had a fever of 105 for days. The paralysis was total in both legs and his arms, though movable, were too weak to hold anything. He couldn't swallow and his speech was undecipherable grunts or groans. He was fed through a tube down his nose after his veins collapsed so IV needles wouldn't penetrate them. I found his room vacant and in near panic sought a nurse. Down the hall two nurses’ aides stood chatting about nail polish colors beside a gurney with a dead body draped in a white sheet. I didn't think it was Walt but was too afraid to ask. Then a nurse I came to like very much came over to me and said Walt had been moved to another room. My fear was not without basis as three people had died that week. While I was still quarantined Walt's coworkers came to the house one noon and presented a savings book with $720.00 on deposit. They also washed all the windows and put up the storm windows but declined to touch any of the sandwiches I prepared for them. The neighbors were supportive in leaving food for me; the bell would ring and I'd go to the door to find a casserole or something in a dish on the porch. They'd give a friendly wave and chat a bit from twenty or more feet away. Polio was greatly feared like the plagues of the middle ages - or the worst fears of AIDs today. After two weeks I finally was asked to come to the hospital as a volunteer to supplement the overworked all volunteer nursing staff. Like them I put in very busy twelve hour days. Squeezing oranges was a never ending chore that filled any otherwise idle moments. There was only one part time physical therapist for a whole floor of patients and I helped exercise three patients and occasionally hot packed them and others. I didn't drive and it was a long hour and a half bus ride with a transfer downtown to get to and from the hospital. I left home at 10:30 AM and got back at 1:30 AM. This was complicated by the fact that I am especially vulnerable to motion sickness when pregnant. I waited until Walt had been hospitalized seven weeks before telling him or our folks that I was pregnant. Walt was very pleased and took it as further incentive to recover and take care of his growing family. My father was pleased but concerned; mother was anxious but both were quick to assure me of their support. Walt's folks heard the news with deadly silence. Dad Krueger viewed this as a serious complication of an already tragic situation in which his only son was desperately ill. He was overwhelmed by the fate that had struck his wife and now his son. The onset of the paralysis was swift and dramatic; the recovery was painfully slow and hesitant. The ability to speak more intelligibly came gradually but proved very frustrating for both Walt and the nurses. I was frequently the only one able to decipher his attempts to be understood. Other physical achievements came heartbreakingly slowly. I shall never forget the jubilation as I danced in the hall with Dr. Kunder the evening Walt managed to wiggle a toe. And then I leaned against the wall and slowly sank to the floor sobbing in despair that that was all he could do. I was joined on the floor by my favorite night nurse and the doctor. Being able to swallow was set as a criterion for being able to transfer to Sheltering Arms, the rehab hospital. This seemed a hopeless goal and only a blatant stretching of the truth allowed the transfer to be made. The atmosphere at Sheltering Arms was completely different. Here the accent was on rehabilitation and recovery instead of simple survival. The ward contained a wide spectrum of disabilities and ages. One negative aspect was that it took another two transfers on the bus to get there and took correspondingly longer to make the trip. Dr. Cole was a pleasant, sympathetic man who seemed genuinely interested in his patients as had Dr. Kunder. They stood in sharp contrast to Dr. McCarthy at Anchor Hospital who was never available, was coldly detached and, I now realize, was afraid of catching polio. I went home to Proctor on my birthday to retrieve Ray. Mom had to stay there to take care of the goats and chickens and Dad came back with me to care for the baby while I was at the hospital. That evening my water broke and Dr. Sekhon came right over. The house grew colder and neither Dad nor Sekhon had any idea what to do to get the furnace going again. They hit it off magnificently and chatted through the night. The next morning John Dowdall came over and replaced a blown fuse; the house got warm. Happily, I did not miscarry. Dad and I trimmed the tree in happy anticipation of Walt coming home for the first time at Christmas. Bill Jordan and Bob Kochendorfer built a ramp at the side stairs for his wheelchair. He weighed 110 pounds and looked like someone out of a concentration camp. It was a bitter sweet holiday. Walt's folks joined Dad, Ray and me for the occasion. Walt came home for several more short visits and then he got pneumonia. Everyone was appalled and wondered how he could possibly survive. Until then all contagious patients had to go to Anchor. Walt told me he’d die if he had to go back there. I begged Sekhon to intercede and admit Walt to Bethesda. He did. He spent a month there and was given wonderful care. Then it was back to Sheltering Arms. The guys in his ward formed a most supportive group; they’d kid each other unmercifully and the humor was frequently ribald. Walt has written about some of his friendships. I'll only say I was very happy to have him there and to watch him slowly regain his health. We contributed to the entertainment when the physical therapist showed me how to exercise Walt. By then I was very pregnant and I needed to straddle Walt over his knees. This was done in the open ward amid catcalls, laughter and a profusion of suggestive remarks; they had a wonderful time! Of course, we went along with it too. Before Walt left Sheltering Arms, Dr. Cole called me in, sat me down and gently told me some terrible news. He said Walt had been so damaged by the polio that he lacked the ability to fight disease and probably wouldn't live beyond a year. Dr. Cole felt Walt's recovery from pneumonia had been miraculous. I needed to share this news with my mother; she had been a nurse and I was sure would take the news in her calm, matter of fact way. We didn't tell my Dad or Walt’s folks because we knew it would devastate them. I didn't want Walt to know; he'd fought so hard to live. Only when Walt had survived to retirement age could I tell him that dark prognosis. The doctor proved to be only half right; Walt did get pneumonia every spring and fall for many years until the pneumonia shot became available about five years before he retired. Walt adamantly refused to go to the hospital; we had oxygen, antibiotics and lots of TLC, but Dr. Sekhon was quick to point out that in case of heart problems or other emergency he’d be better off in the hospital. Walt countered that his schedule was in conflict with the hospital’s and the diet at home was more compatible to his needs. With great trepidation I sided with Walt because I loved him and I knew it was his strong will that kept him alive. But it was very stressful and I worried a lot about whether it was the right thing to do. It was not easy to provide the care Walt needed. Therapy exercises required an uninterrupted hour and a half twice each day. Ray was about 20 months old and had been the star of the show; it was difficult for him to share me with this stranger. The exercises were impossible to perform with Ray in the room. How I wished for a fenced in yard that summer because Ray had a passion for taking off into the hills with his dog, Teddy. My mother reminded me of how she kept Eddie and me safe at the lake; I tied a long rope around the maple tree and fastened one end to the dog and the other end to Ray. They were happy and I knew they were safe. Walt had resolved to get back to work before our daughter was born. He succeeded! He was to return to work for half days but the most difficult part was the getting there and the return trip home so he was back on a full time schedule very quickly. At first his supervisor, Emil Grieshaber, who lived a block away from us would drive him to and from work. Walt's Dad had hand controls installed in the car so he could regain some independence. After all those countless hours of waiting for and riding busses I was very eager to learn to drive. Walt taught me. I took over the task of getting him to and from work until he got a special parking place close enough that he could manage on his own. Walter and Karin Krueger lived happily ever after. Unearthing the Forgotten Flu: Spanish Flu in Clay County