|

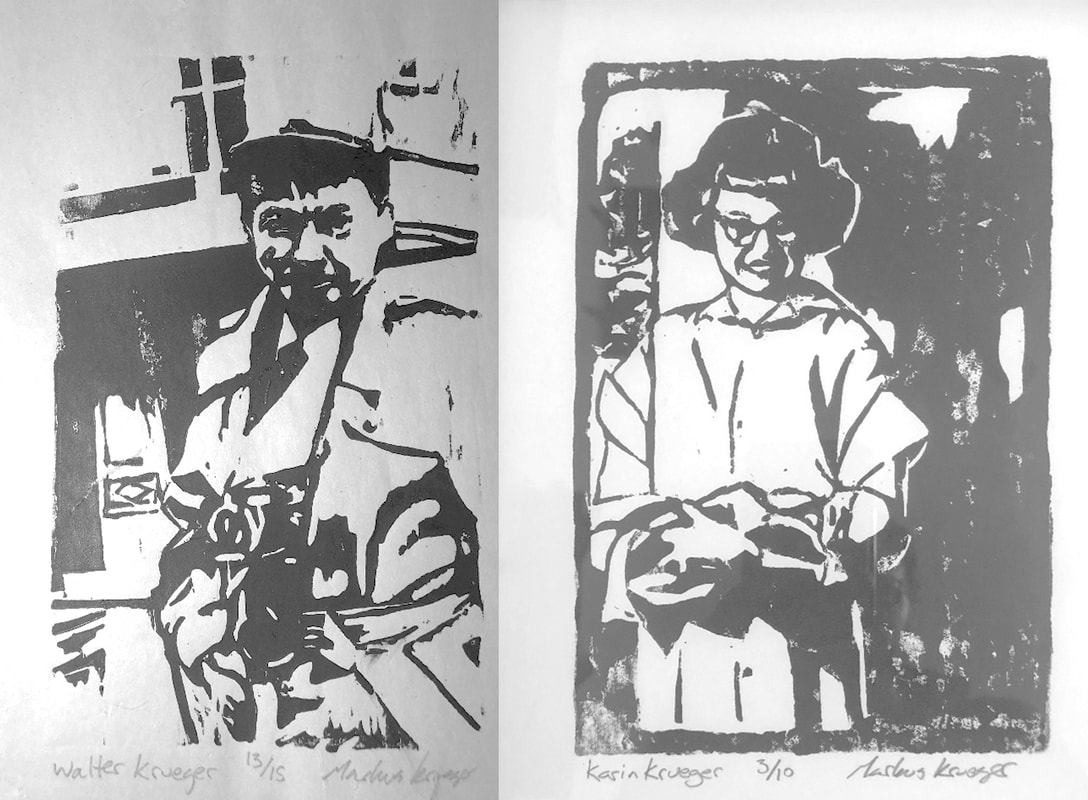

Walter and Karin Krueger in the 1952-53 Polio Epidemic

Markus Krueger March 26, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * I remember when I was not yet ten, my grandpa and grandma, Walter and Karin Krueger, wrote up their life stories. They kept working on it until grandpa’s was 80 pages and grandma’s was 122. Everyone take note: this is the best possible gift anyone can give to their loved ones. As I read the pages, in their words, I remember their stories and I hear their voices. My feisty grandma Karin had the Scandinavian accent so often imitated when poking fun at Minnesotans. Walter’s voice cannot be imitated. In 1952, polio deadened his speaking muscles. In time, he trained different muscles in his throat to move and contract and vibrate with the breath he could muster from the quarter of a lung that still functioned. His voice was raspy, deep, kind of (but not exactly) like what you hear coming out of an old fast foot drive-thru intercom. You and I cannot make the same noises. He was athletic as a young man growing up in Fargo. Not after 1952. Actually, I take that back. Every little thing he did required athleticism. Polio deadened his leg muscles, so he learned to walk by locking his legs straight and propelling himself forward using some still-living ankle muscles on the tops of his feet. All of his children and grandchildren associate him with his crutches. They were with him always, almost extensions of himself. He could not move without them and yet he could practically juggle with them. Years after his death, as several of his descendants were talking about how we have his crutches or pieces of them as mementos of him, my dad pointed out how much his father hated his crutches. But what Walt Krueger saw as a symbol of his disability, those who knew him saw as symbols of his adaptability and tenacity. Or maybe we just like them because they remind us of him. Heck, he’s probably the reason I wear so much plaid. He was a quiet man, perhaps since talking could be difficult for him and those who did not know him could often not understand him. We listened carefully when he spoke because if he chose to say it, it must be worth listening to. That, and what he said was usually smart – he was, after all, an industrial chemist for 3M responsible for inventions like the reflective lettering you see on highway signs and, also, the tape on disposable diapers. But as I get older, what I admire most about Walt Krueger is his patience. And the reason I admire him for his patience is because he was not by nature a patient man. In fact, I think he spent much of his life frustrated, irritated and exasperated. Frustrated that the McDonald’s drive-thru guy can’t understand his order. Irritated that he’s trying not to get toppled over by his grandkids who are running around like crazy people. Exasperated that he wants to go inside a building but the steps leading to the door each look ten feet tall. Patience was forced upon him. He could not scream out, or jump up and down in a tantrum, or physically overpower a misbehaving kid, or go for a run to let off some steam. He handled obstacle after obstacle quietly, persistently, using his engineer’s mind to adapt the world to himself and retraining his body to do tasks that everyone else takes for granted…or, as I often saw him deal with obstacles, scowl, roll his eyes, and hrumph as if saying to himself “let it go. It’s not worth the effort.” When I feel impatient, I look to Walt Krueger’s example for strength. The following paragraphs are excerpts from the unpublished memoirs of Karin and Walter Krueger describing the Polio Epidemic of 1952-53. Walter Krueger: When I had been at 3M for a year I went for a vacation to Wisconsin. Karin’s Aunt Evelyn Bonin and family were at Antigo and we stayed with them for a few days. We stopped at Duluth on the way home and left Ray [their young son] with Karin’s folks. We came home to St. Paul and went to visit the Walker Art Center. We were going to go back to Duluth on Sunday to retrieve Ray and settle back into our routine. It was not to be. I awoke Sunday morning feeling queasy and wondered if it was something I’d eaten the previous evening. I went to bring in the paper and found it difficult to coordinate. I felt a growing panic as I realized something was wrong. I called Dr. Sekhon and was distressed to find my voice didn’t work very well. I awakened Karin and she tried to arrange transportation to Anchor Hospital. I vaguely remember stumbling into Anchor Hospital supported by Karin and our neighbor, John Dowdall. Neither cabs, ambulance or police would handle such a high risk passenger as a suspected polio patient. It had much the same respect, or even greater, than the fear now associated with AIDS. [note: this was written at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1990.] I remember lying on the gurney awaiting the outcome of the analysis of the spinal tap. It is impossible for me to separate real memory from hallucinations for the days or even weeks that followed. 1952-3 was the last epidemic year for polio due to the development of effective serums for immunization. That year the patient load was heavy and staffs were strained to the breaking point trying to cope. Karin was there all day every day serving as a private nurse to supplement the overworked staff. My condition deteriorated to the point that it was recommended that I be put in an “iron lung.” I felt that going into the lung was a one way trip so for the sake of my morale they elected to delay that move for as long as possible. I did manage to escape that. I was unable to swallow and was fed through a tube down my nose. Speech was virtually unintelligible. Leg movement was gone and my arms were too weak to hold up a comic book. Hot pack sessions and exercise therapy became the highlights of the day. Eating was the goal to achieve to graduate from Anchor to Sheltering Arms where convalescent therapy would begin. The head doctor was a pompous politician with a bright, irrelevant remark for everyone. His two assistants were both hard working young doctors but one was all business and as impersonal as a rock. The other was as compassionate as he was conscientious; a literal lifesaver. Eventually I did arrive at Sheltering Arms. A nurse named “Donney” took care of our ward; she reminded me very much of my Aunt Alma. Dr. Wallace Cole was a distinguished gentleman with a lot of empathy for his patients. As strength came back to my arms I started to relearn to walk. This was a precarious adventure on legs that would lock but otherwise had little response. Just getting up from a wheel chair was a gymnastic feat of no mean proportion. For a time I envied a fellow whose legs worked great but whose arms and hands were useless. I soon grew to appreciate that getting there was no use if you couldn’t do anything when you got there. I was sustained all through this trial by Karin’s faithful daily appearance and support. I was determined to resume my career and support my family. The suspicion that I might never regain the use of my legs or swallow was slow to dawn and emotional adjustment came gradually. I took Karin’s presence for granted without regard for the effort and sacrifice she made in riding a chain of busses across town twice a day. Her dad brought Ray to St. Paul and he baby sat all day while Karin was with me. I was allowed to go home for a few days at Christmas time. I was down to 110 pounds and looked like a Belsen or Auschwitz survivor. I came down with Pneumonia and only Dr. Sekhon’s valiant effort got me into Bethesda Hospital instead of being returned to Anchor. The battle to breath was to become a regular event for several years. At least once each spring and fall I’d catch a cold that often turned into pneumonia. I pleaded to remain at home for these bouts because the regimen at the hospital wasn’t in synch with my needs. Good intentioned dieticians never seemed able to understand the difference between chewing and swallowing. I couldn’t make them believe that hamburger and mashed potatoes were among the hardest things to swallow. Again Dr. Sekhon cooperated but he always worried that I might need special equipment only available at the hospital. I started back to work half days but it was the coming and going that was the most difficult. Soon I was going full time. MY coworkers were very supportive. When I was just beginning to recover they took up a collection for me at the lab that gave us a savings account of $700.00. I have always been grateful to 3M they took back this person with one year’s service and hardly able to walk. Many of my ward mates at the hospital were facing trying to start new careers because their old jobs were now beyond their abilities. Karin Emberg Krueger: Sunday morning Walt got up to get the paper and discovered he was very weak and dizzy. He went to bed while I called Dr. Sekhon. He told me to get Walt to Anchor Hospital. When I mentioned polio neither cabs nor police would come near us. So I ran to the neighbors and found most of them were at church. Clarence Etter backed away from me in horror; Carol Anne was about due and he was afraid. John Dowdall was in the back yard and when he learned of the problem immediately offered his help -dear, dear man! Between us we dragged Walt to John's car and we went to Anchor. The whole afternoon passed before we got the diagnosis of polio confirmed. I signed two papers; one for a tracheotomy and the other for an Iron Lung. Then they sent me home with John. At dawn the next morning I got a call to come as quickly as I could because Walt was dying. The cab came so soon I was buttoning skirt and blouse as I ran down the stairs to the cab. We sped to the hospital only to be told that the immediate crisis was past. After a short 20 minutes with him they sent me home again under a two-week quarantine. A week later Walt had another crisis - he'd had a fever of 105 for days. The paralysis was total in both legs and his arms, though movable, were too weak to hold anything. He couldn't swallow and his speech was undecipherable grunts or groans. He was fed through a tube down his nose after his veins collapsed so IV needles wouldn't penetrate them. I found his room vacant and in near panic sought a nurse. Down the hall two nurses’ aides stood chatting about nail polish colors beside a gurney with a dead body draped in a white sheet. I didn't think it was Walt but was too afraid to ask. Then a nurse I came to like very much came over to me and said Walt had been moved to another room. My fear was not without basis as three people had died that week. While I was still quarantined Walt's coworkers came to the house one noon and presented a savings book with $720.00 on deposit. They also washed all the windows and put up the storm windows but declined to touch any of the sandwiches I prepared for them. The neighbors were supportive in leaving food for me; the bell would ring and I'd go to the door to find a casserole or something in a dish on the porch. They'd give a friendly wave and chat a bit from twenty or more feet away. Polio was greatly feared like the plagues of the middle ages - or the worst fears of AIDs today. After two weeks I finally was asked to come to the hospital as a volunteer to supplement the overworked all volunteer nursing staff. Like them I put in very busy twelve hour days. Squeezing oranges was a never ending chore that filled any otherwise idle moments. There was only one part time physical therapist for a whole floor of patients and I helped exercise three patients and occasionally hot packed them and others. I didn't drive and it was a long hour and a half bus ride with a transfer downtown to get to and from the hospital. I left home at 10:30 AM and got back at 1:30 AM. This was complicated by the fact that I am especially vulnerable to motion sickness when pregnant. I waited until Walt had been hospitalized seven weeks before telling him or our folks that I was pregnant. Walt was very pleased and took it as further incentive to recover and take care of his growing family. My father was pleased but concerned; mother was anxious but both were quick to assure me of their support. Walt's folks heard the news with deadly silence. Dad Krueger viewed this as a serious complication of an already tragic situation in which his only son was desperately ill. He was overwhelmed by the fate that had struck his wife and now his son. The onset of the paralysis was swift and dramatic; the recovery was painfully slow and hesitant. The ability to speak more intelligibly came gradually but proved very frustrating for both Walt and the nurses. I was frequently the only one able to decipher his attempts to be understood. Other physical achievements came heartbreakingly slowly. I shall never forget the jubilation as I danced in the hall with Dr. Kunder the evening Walt managed to wiggle a toe. And then I leaned against the wall and slowly sank to the floor sobbing in despair that that was all he could do. I was joined on the floor by my favorite night nurse and the doctor. Being able to swallow was set as a criterion for being able to transfer to Sheltering Arms, the rehab hospital. This seemed a hopeless goal and only a blatant stretching of the truth allowed the transfer to be made. The atmosphere at Sheltering Arms was completely different. Here the accent was on rehabilitation and recovery instead of simple survival. The ward contained a wide spectrum of disabilities and ages. One negative aspect was that it took another two transfers on the bus to get there and took correspondingly longer to make the trip. Dr. Cole was a pleasant, sympathetic man who seemed genuinely interested in his patients as had Dr. Kunder. They stood in sharp contrast to Dr. McCarthy at Anchor Hospital who was never available, was coldly detached and, I now realize, was afraid of catching polio. I went home to Proctor on my birthday to retrieve Ray. Mom had to stay there to take care of the goats and chickens and Dad came back with me to care for the baby while I was at the hospital. That evening my water broke and Dr. Sekhon came right over. The house grew colder and neither Dad nor Sekhon had any idea what to do to get the furnace going again. They hit it off magnificently and chatted through the night. The next morning John Dowdall came over and replaced a blown fuse; the house got warm. Happily, I did not miscarry. Dad and I trimmed the tree in happy anticipation of Walt coming home for the first time at Christmas. Bill Jordan and Bob Kochendorfer built a ramp at the side stairs for his wheelchair. He weighed 110 pounds and looked like someone out of a concentration camp. It was a bitter sweet holiday. Walt's folks joined Dad, Ray and me for the occasion. Walt came home for several more short visits and then he got pneumonia. Everyone was appalled and wondered how he could possibly survive. Until then all contagious patients had to go to Anchor. Walt told me he’d die if he had to go back there. I begged Sekhon to intercede and admit Walt to Bethesda. He did. He spent a month there and was given wonderful care. Then it was back to Sheltering Arms. The guys in his ward formed a most supportive group; they’d kid each other unmercifully and the humor was frequently ribald. Walt has written about some of his friendships. I'll only say I was very happy to have him there and to watch him slowly regain his health. We contributed to the entertainment when the physical therapist showed me how to exercise Walt. By then I was very pregnant and I needed to straddle Walt over his knees. This was done in the open ward amid catcalls, laughter and a profusion of suggestive remarks; they had a wonderful time! Of course, we went along with it too. Before Walt left Sheltering Arms, Dr. Cole called me in, sat me down and gently told me some terrible news. He said Walt had been so damaged by the polio that he lacked the ability to fight disease and probably wouldn't live beyond a year. Dr. Cole felt Walt's recovery from pneumonia had been miraculous. I needed to share this news with my mother; she had been a nurse and I was sure would take the news in her calm, matter of fact way. We didn't tell my Dad or Walt’s folks because we knew it would devastate them. I didn't want Walt to know; he'd fought so hard to live. Only when Walt had survived to retirement age could I tell him that dark prognosis. The doctor proved to be only half right; Walt did get pneumonia every spring and fall for many years until the pneumonia shot became available about five years before he retired. Walt adamantly refused to go to the hospital; we had oxygen, antibiotics and lots of TLC, but Dr. Sekhon was quick to point out that in case of heart problems or other emergency he’d be better off in the hospital. Walt countered that his schedule was in conflict with the hospital’s and the diet at home was more compatible to his needs. With great trepidation I sided with Walt because I loved him and I knew it was his strong will that kept him alive. But it was very stressful and I worried a lot about whether it was the right thing to do. It was not easy to provide the care Walt needed. Therapy exercises required an uninterrupted hour and a half twice each day. Ray was about 20 months old and had been the star of the show; it was difficult for him to share me with this stranger. The exercises were impossible to perform with Ray in the room. How I wished for a fenced in yard that summer because Ray had a passion for taking off into the hills with his dog, Teddy. My mother reminded me of how she kept Eddie and me safe at the lake; I tied a long rope around the maple tree and fastened one end to the dog and the other end to Ray. They were happy and I knew they were safe. Walt had resolved to get back to work before our daughter was born. He succeeded! He was to return to work for half days but the most difficult part was the getting there and the return trip home so he was back on a full time schedule very quickly. At first his supervisor, Emil Grieshaber, who lived a block away from us would drive him to and from work. Walt's Dad had hand controls installed in the car so he could regain some independence. After all those countless hours of waiting for and riding busses I was very eager to learn to drive. Walt taught me. I took over the task of getting him to and from work until he got a special parking place close enough that he could manage on his own. Walter and Karin Krueger lived happily ever after.

2 Comments

Unearthing the Forgotten Flu: Spanish Flu in Clay County

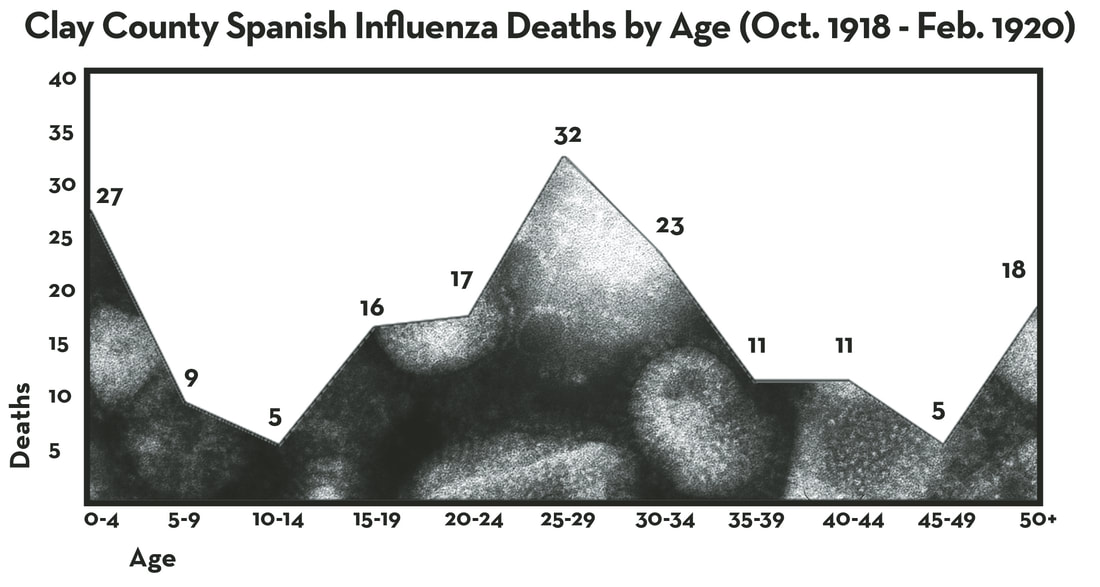

Davin Wait March 1, 2018 -additional research by Mark Peihl & Pamela Burkhardt * * * * * * * * * * There’s something of a local legend here about Concordia College’s fall quarantine in 1918. The story goes that Concordia’s President J.A. Aasgaard closed the perimeter on October 8, and as a result Concordia’s student body was largely spared from the horrifying pandemic that followed: the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic better known as La Grippe or Spanish Flu. A November issue of the campus newspaper The Crescent noted the quarantine's success and observed the following: “It is evident that our students are so abnormally healthy that even the ‘Flu’ germ shuns them.” The only recorded campus death also seemed to reinforce the wisdom of the decision. Apparently a female student broke quarantine and went home. She contracted the disease at some point during her trip and died shortly thereafter. Erling Rolfsrud included the story in his Cobber Chronicle (1966) without sharing his source and Carroll Engelhardt repeated the story in On Firm Foundation Grounded (1991). The consensus among scientists and Spanish Flu historians today would support Aasgaard’s choice. Quarantine was about the best available recourse. But, assuming the quarantine was executed as ordered and recorded, it was still probably lifted too early to have made a significant impact on the community’s overall health. The perimeter was opened the same day another Moorhead woman, Esther Anstrup (23), died from the flu. Three additional Moorhead residents, all in their 20s, would die from the flu that month and twenty-nine more people would die in the county after November 7 — when the quarantine was lifted — as the flu moved through smaller towns and rural areas. Twenty-six more would die in December. By the end of May 1919, Clay County had lost 151 people. In other words, Concordia may have weathered the storm, but that was more likely due to the peculiarities of Spanish Influenza than an effective quarantine. That is, Spanish Influenza found its most vulnerable hosts in people usually unscathed by influenza: healthy people in their 20s and 30s (just a little older than most college students). In fact, this was one of the clear and more horrifying markers of the disease. Recent work in flu genomics is beginning to explain this peculiarity, as well — but first some history. * * * * * Spanish Influenza had arrived in Minnesota at the end of September, just as the Meuse-Argonne offensive was taking form overseas. The US Surgeon General announced it on September 25 after several Army recruits temporarily housed on the University of Minnesota campus fell ill, but it had broken out at a military funeral in Wells, Minnesota, a week earlier. Walter Paulson was being buried. He’d died of pneumonia serving in the Navy. His brother, Private Raymond Paulson, was among the group watching him go in the ground. Within weeks Raymond, his sister Anna, and the presiding Reverend C.W. Gilman were also dead. Locals here would have first heard about the flu in news reports about military casualties. When it was apparent the disease was moving through America, some of our area newspapers would note its westward path as it moved toward us in Minnesota. This allowed people in the Red River Valley some time to prepare, but these stories were also lost in war headlines, a mid-term election, a Minnesota wildfire, and yet another liberty loan drive. Even so, not long after its presence was announced in Minnesota, Moorhead Normal School postponed the fall semester. Then the first cases in Fargo-Moorhead were reported Friday, October 4. On Monday, October 7, infant Selma Johanna Hanson died in Moorhead. She was the first flu casualty in the county. The following day three more women joined her – Maria Letigia Altobelli (28), Ella Anderson (45), and Annie Jane Schilling (25). Moorhead’s city council banned public gatherings and closed schools. On Wednesday, with 2,500 cases reported in Fargo-Moorhead-Dilworth, Concordia closed its perimeter and continued with business as usual – the best they could – within the confines. When they opened those perimeters a month later, they had no idea that the disease would eat at our community for another 15 months. In Clay County, 174 people died from the flu or flu-related diseases. The population at the time numbered about 21,000 (0.8% of the population died from the flu or flu-related disease). Moorhead lost 68 people (1.2% of the population), Hawley lost 12 people (2.8%), Barnesville and Dilworth lost 10 people (.66% and 1.25%, respectively), and Ulen lost 8 people (1.3%). Outside of the transportation and population centers of Moorhead and Dilworth, the communities of Goose Prairie, Ulen, and Highland Grove townships were particularly hit hard (24 deaths total), but Hawley Township wasn’t far behind (16 deaths). Barnesville’s flu deaths were evenly scattered throughout the pandemic and didn’t begin until October 16. When the flu fatalities are mapped, it’s fairly clear that the disease made its landing in Fargo-Moorhead-Dilworth, and probably by rail. Many in these communities worked on or with the railroads, including the heavily trafficked Northern Pacific Railway station in Dilworth. The first 15 flu-related deaths of Clay County occurred in Moorhead and Dilworth. The Italian population of Moorhead and Dilworth suffered early and disproportionately, too. Five of the first fifteen deaths appear to have struck Italians. Ethnic and class isolation at the time may explain it. Sex didn’t appear to be a factor: death rates among men and women were about the same. However, pregnancy was markedly more dangerous than usual. A definitive number doesn’t exist, but medical historian John M. Barry cites studies that put the global fatality rate among infected pregnant women between 23-71%. About 40% of Clay County’s deaths were young adult women, miscarriages, and stillbirths. Little Selma Hanson, the first influenza casualty here, was followed four days later by her mother Rachel (21). At the end of November, Agnes Wilinski was stillborn in Moorhead. Two days later her mother Hattie (26) followed. In March of 1919, Medalia Stockwell (25) died of flu and pneumonia along with the child she was carrying. Dilworth suffered its 10 fatalities all in the last three weeks of October – though it should be noted that deaths after those first two weeks, even among people in rural areas, were more likely to occur in Fargo-Moorhead hospitals. Dilworth only had one Red Cross nurse, Louise Christensen, and a few volunteers. On October 19, Christensen wrote to her supervisor, “We are very, very busy, have 24 patients in hospital now. Have dismissed about 15, two have died, and perhaps one or two died last night.” Her estimate would have included Louise Rae (45), who had died October 18. Dilworth counted four more deaths in the following ten days. Though Ulen, Barnesville, Hitterdal, Hawley, and Glyndon closed their schools and banned or limited public gatherings from early October through early November, the disease still spread to more isolated, rural areas. The first rural deaths began in Morken Township on October 14 and Barnesville and Skree Township on October 16. Like the northeastern corner of the county near Ulen, southeastern Skree and Parke townships near Rollag suffered a disproportionate number of flu-related deaths (6 and 4, respectively). Ulen registered its first death on October 18 – even though J.T. Johnson reported that same day from Ulen to the Moorhead Daily News that there was little illness there. Another Ulen death followed on Halloween. The Ulen-Hitterdal area would see 20 more that year. Hawley held out for a while. Perry Pederson (30) lost his battle on October 25 and an infant, Clarice Aune, died on November 25. There were several deaths in neighboring rural townships, suggesting attempts at quarantine and home care, but December would bring a deadly winter for Hawley. Twelve villagers would die from the flu by May 18, 1919. Ten others would die in the four townships surrounding it (Hawley, Cromwell, Highland Grove, and Eglon). The region was spared from the second wave that began late December, 1919. The southwestern corner of the county suffered several losses as well, beginning in Holy Cross Township on October 29 with Lynn Peterson (25). Another followed there on November 6, bringing a relatively high concentration of November deaths. Overall, Holy Cross registered 5 deaths during the pandemic, Alliance 3, Elmwood 2, and Kurtz 1. That region suffered during both waves, ending with Valine Larson’s death on February 19, 1920, at the age of 29. Georgetown appears to have fared well. Though the village reported infection, and census records show a notable population dip in 1920 (likely attributed to war displacement and Prohibition-inspired urban migration), only one death was registered there during the pandemic: Wells Bristol (56), near the very end, on February 24, 1920. The four townships surrounding Georgetown registered only three deaths (2 in Morken and 1 in Kragnes). The old trading post seems to have been isolated enough to withstand the disease. The final flu casualty in the county occurred on February 29. Leap Day. A child born in Parke Township died only several hours later. * * * * * The result of the prolonged tragedy has been measured in a few sobering ways. There were probably more than 500 million global infections in just under two years (between 25-35% of the population). Though a large majority of those infected experienced nothing more than a few sleepy days of cough and fever, there were probably 50-100 million global deaths (compare this to the 17 million casualties of World War I). This amounted to 2.5-5% of the global population. Much of the developed world lost around 2% of their populations. Fatality rates in underdeveloped countries, particularly those in Asia, were much higher. Despite similar infection rates, Americans were relatively immune at 675,000 deaths (0.655% of the population), with some wide disparities. For example, a Metropolitan Life Insurance Company study of Americans aged 25 to 45 found that 3.26% of industrial workers and 6% of coal miners died. Life expectancy in the U.S. dropped 12 years in 1918. In Minnesota, an estimated 250,000 were infected and nearly 12,000 died (0.5% of the state population). More than half of Minnesota’s 3,700 war casualties suffered flu-related deaths (2,300, or 62%). In November of 1918, deaths in the state outnumbered births for the first time. Clay County endured at least 174 deaths in a population of 21,000 (some were undoubtedly uncounted and/or unreported) during the pandemic's first 18 months. The average age of those who died in Clay County was 26.3 years. Using the life expectancy in the U.S. before the war (about 51 years), that means we lost about 4,333 years of human life in Clay County. Of the 64 Clay County residents who died in the military, 29 died from flu-related illnesses – bringing Clay County’s total flu casualties to 203 people. Our total years lost in the county was closer to 5,000. We lost a lot of life. The most frequent victims of the Spanish Influenza pandemic were those between 25-35 years old. Many medical researchers have attributed this peculiarity to the strong immune systems of the inflicted. Apparently too strong. When cells in the human body are threatened by pathogens like the Spanish Influenza virus, their first defenses are interferons, cytokine proteins that communicate the need for defense to nearby cells. White blood cells (or leukocytes) follow, disarming/killing/consuming these invaders and infected or dead cells. As you can imagine, all of this activity wreaks havoc on tissues, leaving them inflamed and the host fevered. Inflammation is even part of the defense: if more blood is delivered to the site of infection, more leukocytes are available to fight. But when that defense is moving too strong in too concentrated of an area, it damages necessary human tissues in what’s called a ‘cytokine storm’ (the war analogy here might be friendly fire or total annihilation). Spanish Influenza triggered these cytokine storms and left a battlefield in the lungs, spaces now filled with liquid and dead tissues and offering little respiration or defense. In fatal cases, the flu killed by hypoxia. In other words, people drowned to death in their own fluids. This is why several fatalities were marked by what was called “heliotrope cyanosis,” a bluing of the skin from oxygen deprivation. However, dangers lay ahead even for those who were able to shake the flu virus. When other pathogens — like Streptococcus Pneumoniae — that would otherwise be routinely destroyed in the upper respiratory system came upon this battlefield, they were be able to stroll right through it to the deeper tissues of the lower lungs. The secondary infections that followed flu infection, typically viral and bacterial pneumonia, are widely believed to have killed more people than the flu itself. * * * * * Given the impact of the pandemic and the continued threat we face from influenza, scientists are still searching for answers. Consensus is out on the question of locating the outbreak’s “spill-over event” or “patient zero.” There was so much movement on this planet at the time, it’s an almost impossible task. Some point to a 1916 English outbreak of “Purulent Bronchitis.” Others to a 1917 outbreak in France, possibly carried to the Western Front by the Chinese Labor Corps. The strongest case seems to point to Haskell County, Kansas, where a rural outbreak moved to the Army’s nearby Camp Funston and filled the hospital and barracks with sick soldiers in March, 1918. As journalist and historian Laura Spinney puts it, about the only real consensus is that this was a deadly pandemic that picked up its name because neutral Spain was the only place journalists were willing to report on it. However, the abandoned Ph.D. of a Swedish virology student at the University of Iowa in 1951 has recently become a touchstone moment in better understanding the Spanish Influenza. Johan Hultin was looking for a dissertation idea when a guest lecturer offhandedly remarked that someone should travel north and find a frozen (preserved) sample of Spanish Influenza in the North American permafrost. Hultin accepted the challenge, flew to Alaska, found two destroyed graveyards, trekked 6 miles through soggy tundra, and came to a third at Brevig Mission. Here the flu had killed 72 people. All but three children. But the graveyard looked promising. After consulting the village’s matriarch and council, Hultin was given permission to dig through the mass grave that had been filled thirty-three years prior. He promised that the villagers’ sacrifice would help prevent the tragedy again. He found his sample six feet down, frozen, and took it back to Iowa. Then, after several tests, he ran out of tissues. The sample was gone and he abandoned his Ph.D. After some time off he returned to earn an M.D. Forty five years later, Jeffrey Taubenberger at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology was making waves in the world of virology. He’d sequenced segments of Spanish Infleunza that had been preserved in the National Tissue Repository, but he’d encountered the same problem: not enough tissues. Fortunately, Hultin was still cued into the medical world and he reached out to Taubenberger. With the Institute’s funding, Hultin returned to Brevig Mission in August, 1997, to conduct a second excavation. The village had known of his previous attempt and the village matriarch was the granddaughter of the woman he’d appealed to in 1951. Once again, the council gave him permission; and, once again, Hultin found his sample. He took a larger piece. In 2005, the full genome was sequenced, including that of the virus’s important surface H- and N- glycoproteins (Hemagglutinen and Neuraminidase are the flu’s primary weapons in both entering and leaving human cells; the proteins' different strains are identified with numbers). Taubenberger and his team determined that Spanish Influenza, an H1N1 virus, was likely the progenitor of current human and swine influenza A strains (H1N1 and H3N2), as well as the extinct H2N2 virus that circulated in the 1950s and ‘60s. They also confirmed earlier hypotheses that the pathogen had made a zoonotic leap, mutating from an animal strain and spilling over into the human population. This was valuable information, of course, but many didn’t see a smoking gun. Still not much to explain the pandemic’s origin or virulence. Then, over the last decade, Dr. Michael Worobey took the problem from a different perspective. Instead of searching within the flu’s genome, he set it beside other flu genomes to determine its rate of mutation and isolate the divergences or branches on its phylogenetic tree. His process, using “molecular clocks” and thousands of flu gene sequences, is leading to a new understanding of the flu, particularly in understanding the importance of childhood exposure and immunities. The 1918 H1N1 flu had been so lethal to 20- and 30-year olds because their early exposures had been to a flu of markedly different surface proteins: H3N8. Other demographics, like teens and older adults, had some defense following their childhood exposure to an H1N8 flu. As elderly Americans at the time had grown up with a separate H1N1 flu, they had in many ways already fought the battle. -Davin Wait, HCSCC -additional research by Mark Peihl, HCSCC |

Visit Us

|

Resources

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed