|

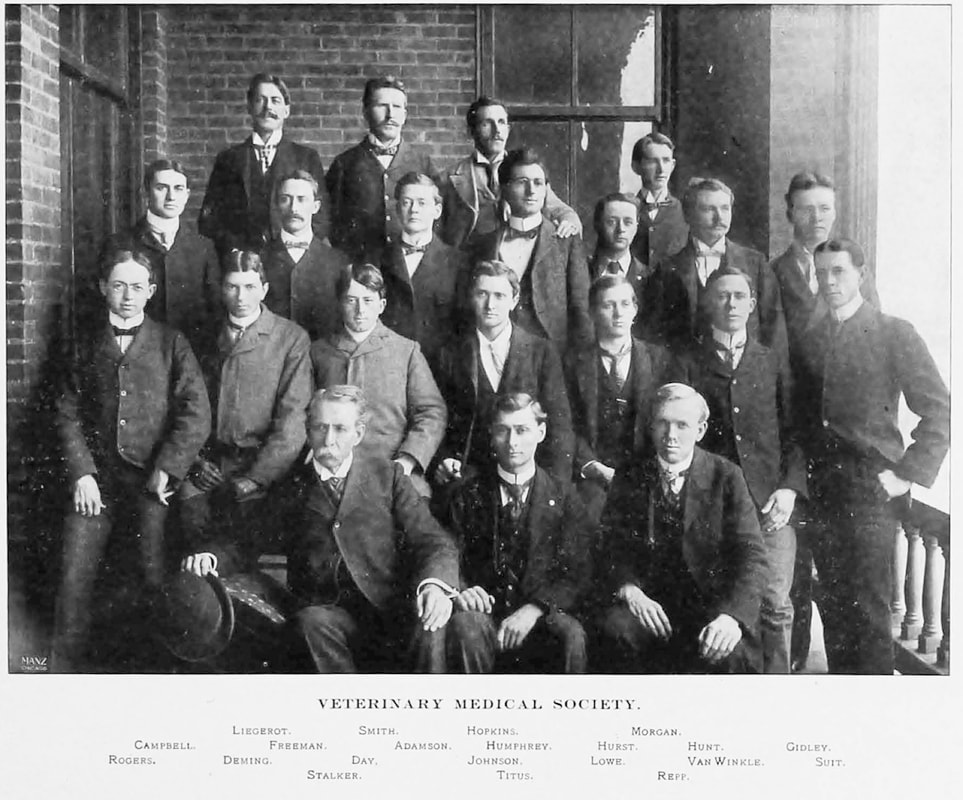

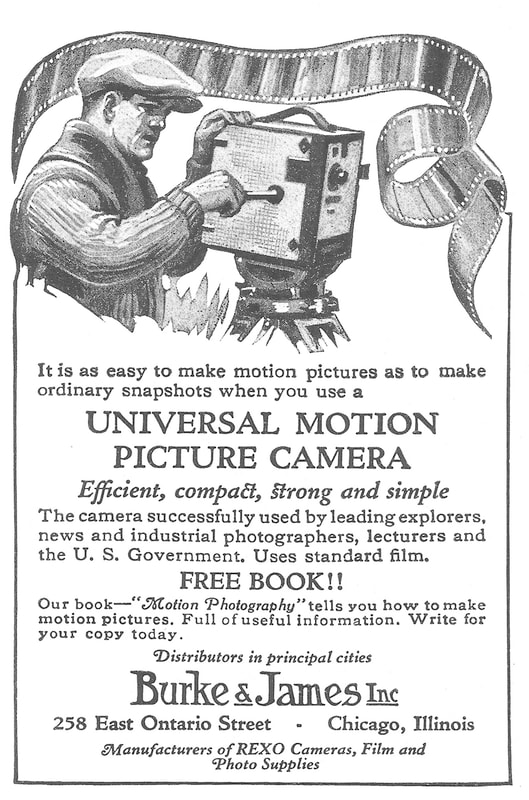

Dr. Humphrey's Movies By Davin Wait, HCSCC Communications Manager from The Hourglass, Fall 2017 * * * * * * * * * * At this moment, HCSCC possesses five different formats of the same 12 minutes of film footage previously owned by former Moorhead physician, surgeon, and five-time mayor Dr. Edward W. Humphrey. The footage was primarily filmed in the spring and summer of 1917, and it now exists in our archives in the original 35mm reel, the 16mm reel onto which his son Dr. George Humphrey transferred the original and then sent to us in 1988, the ¾” videotape WDAY produced from that 16mm stock in 1989, a 1996 VHS recording produced by MSUM’s Bob Schieffer and featuring our archivist Mark Peihl’s commentary, and the current collection of digital files (.mp4, .mov, etc.) swirling around on YouTube, Facebook, and our shared digital spaces. As our tendency to commemorate centennials would go, it’s worth noting that the footage turned one hundred years old last summer. It’s already proven itself a valuable asset to both CCHS and HCSCC, but I’d like to return to the material as a focal point for a brief introduction to Humphrey, some of the earliest years of film in Clay County, and the communities that were taking shape in 1917, the year that brought the War To End War and immediately preceded the Spanish Influenza. Given the ephemeral nature of film, it’s also an opportunity to reflect on the struggles of preserving the past and translating it for the present and future. Edward William Humphrey was born on January 16, 1877, in Reedsburg, Wisconsin, to his father William and his mother, Elizabeth Fischer, a woman who migrated to the U.S. as child with her French parents. Born after his older sister Agnes and before his brother William and younger sister Isabel, Edward moved as a child with his parents to a farm outside of Gary, South Dakota – a small town 30 miles southeast of Watertown and about as close as you can get to the Minnesota border. He grew up there and lived through the tragedy of his young mother’s death in 1887. Humphrey left South Dakota for college in Ames, Iowa, and in 1899 earned a four-year Doctorate of Veterinary Medicine at Iowa State College of Agricultural and Mechanic Arts (formerly Iowa Agricultural College and now Iowa State University). Iowa State was small then, averaging about 70 graduates a year during Humphrey’s stay, but it would have offered an interesting contrast to his farm life in Gary. He likely would have encountered George Washington Carver, the young scientist born into slavery who was teaching and finishing his graduate degree there in 1896. Humphrey also certainly encountered Iowa State’s football coach, Glenn “Pop” Warner, a man whose revolutionary football mind led to his commemoration as the namesake of the youth football league. Humphrey wasn’t the All-American that his 1961 obituary claimed him to be, but he did play for Warner on a solid Iowa State football team in the late-90s (including the three semesters he may not have been enrolled in classes, as University of Nebraska-Kearney professor and Ames historian Dr. Doug Biggs recently shared with me). After earning his degree in Ames, Humphrey traveled a long road in a brief four years before landing in Moorhead. He earned an M.D. in 1902 from the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Hamline University in St. Paul and then interned in Rochester, MN, before practicing briefly in Lidgerwood, North Dakota. By 1903 he was in Moorhead, living at 411 2nd Avenue South, practicing medicine in the Wheeler Land Company block (Front Street and 7th Street S), and married to local woman Edith Vincent. In 1907 he became the chief surgeon at Northwestern Hospital while living with Edith and his brother William, a student, two blocks west. By 1909 he and his wife were living at 428 8th Street South, just across the street from Solomon and Sarah Comstock. In 1913 he opened a practice with Dr. Gilbert Gosslee in north Moorhead; in 1918 he purchased land for what would become his own Moorhead Clinic; and in 1919 he defeated incumbent Nels Melvey in the Moorhead mayoral race on the strength of his popularity in the 3rd ward – the only ward he won. Some evidence suggests that Humphrey’s politics weren’t particularly attuned to the plight of the working classes or poor, but he was a loud voice in the community’s anti-saloon movement and committed to Moorhead's growth. As a business-friendly Democrat who championed several public improvements during his first campaign for mayor and a man with expensive tastes who shared within his circle, he developed many friends and partners in the community. His love for cars and his influence as a doctor in the middle of the Spanish Flu epidemic surely must have raised his profile in the community prior to his election, as well, but his film equipment and that early movie magic might actually have played a larger role. The Moorhead Daily News was already commenting on Humphrey’s home movies in the early spring of 1917. His friend Ed Rudd, of The Daily News, often served as Humphrey’s cameraman, so the physician and surgeon’s early film exploits were well-known in the newsroom. On Thursday, March 29, 1917, it was reported that he and his wife Edith had entertained several guests with their film projector and five newsreels, of “most impressing war pictures.”* *These likely would have been The Universal Animated Weekly, The Hearst International Weekly, Pathe Animated Gazettes, or The Hearst-Pathe News – 5-minute news accounts released in local theatres that tended to offer more spectacle than reporting – but official British and American newsreels wouldn’t have been far behind. According to Criss Kovacs of the National Archives, prior to entering World War I, the U.S. Army Signal Corps spent nearly $3 million to equip and train almost a thousand employees for newsreel production (about $65,000,000 today). The Committee on Public Information (CPI) used much of this footage in its weekly newsreel, the Official War Review, in an effort to drum up public support. A month later on Friday, April 20, The Daily News announced that Humphrey had added to his entertainment collection and purchased a Universal moving picture camera: “with his projection machine makes one of the most complete motion picture outfits extant.” He’d bought the piece in Chicago on a business trip only days before, spending somewhere around $475 on the $300 camera, film, and accessories. Humphrey likely wasn’t considering the political power of film, like the CPI, but he almost immediately set out filming the community, and they responded to that opportunity with enthusiasm. Now, motion pictures were nothing new to the community by then: Fargo had several movie theatres by this time, Moorhead’s Lyceum Theatre had been screening films since December 7, 1910, and a traveling showman had even brought the “Marvelous Cinematoscope” to Moorhead’s Fraternity Hall in May of 1897, the very infancy of moving pictures (see Mark’s article in the January 1997 CCHS newsletter for this account). However, the fact that Humphrey had turned the camera back onto the local community offered something markedly different. He’d just turned Fargo-Moorhead into both the audience and the stars. Only days later, on Monday, April 23, Humphrey filmed “Patriotic Day,” one in a string of nationwide events scheduled to build support for the war. Moorhead’s event had been postponed because of bad weather, but two thousand people gathered at the high school; local children dressed up in red, white, and blue to create a living flag; and the community ran a flag up a 72-foot pole. Humphrey’s neighbor, Solomon Comstock, gave a speech. All of it was captured on Humphrey’s film and the framing of his shots show that he was given prime real estate to record it. Two weeks later, on Monday, May 7, Humphrey recorded a test run of the Moorhead fire department running at “top speed and with full equipment.” Two days after that, about 650 Moorhead Normal School students and about 550 Concordia College students took a break from class and study to march in circles from their classrooms and through the grounds while Humphrey sat outside of Weld Hall and Old Main to record them. Again, the Daily News covered it, with the following headlines: “1200 Students Pose for Movies | Dr. Humphrey Takes Moving Pictures of City’s Students Today | Normal School and Concordia Students Make Excellent Appearance.” We can presume that Humphrey filmed the community for much of the summer of 1917, as his footage runs from mundane shots in his driveway, through the auto polo matches at the Fargo Interstate Fair in July, and to another patriotic WWI gathering for Dedication Day at Concordia in early September. Unfortunately, we can’t be sure of how much footage existed or what we’ve already lost, because much of it decomposed in his Pelican Lake cabin where it sat for years before Humphrey’s son found and donated it to CCHS in 1989. This is also what makes this century footage even more valuable to us as historians. In the early years of film, the nitrocellulose base that was used before the acetate “safety film” was the same general material as guncotton: a cheap, highly combustible, and autocatalytic explosive. This meant that the slightest heat or friction, in almost any setting, could send this film into flames . . . and often did (the 1909 Cinematograph Act in Great Britain required a fire-resisting enclosure, or projection box/booth, for theaters; this is partly why projectors no longer sit in the middle of the auditorium, a much cheaper option for movie houses). Additionally, and this is true of the acetate-based safety films that followed, nitrate film base was often made with immediate durability, not preservation, in mind. So even if the base doesn’t deteriorate on its own, turning into a rust-colored powder, it frequently interacts with heat, humidity, and the emulsion layer (the photosensitive silver layer) in unfortunate ways: separation, growing dry and brittle, decomposing and creating byproduct “bubbles." Add to this the frequency at which film was destroyed for its silver content, including many early Hollywood “lost masterpieces” -- Austrian-American director Erich von Stroheim’s Greed (1924) comes to mind -- and it is amazing that we have the footage that we do. Humphrey went on to win the mayor’s seat in February of 1919, almost assuredly in some part due to the press he received and the relationships he built around his moving pictures. Even so, the movies, his public works projects, and the strong support he received from Moorhead businessmen weren’t enough to help him in 1921, when he waffled on campaigning again and lost his reelection bid to Clarence Evenson. Strangely enough, though, that wasn’t the end of the political magic of those 1917 movies for Humphrey. The footage turned up again in May of 1931 as Moorhead celebrated its 50th anniversary. The Moorhead Theatre (which opened in 1928 and ran the Lyceum out of business the same year) screened the films to show the community what the old days were like (The Daily News got it wrong and said they were 20 years old). Humphrey ran for mayor again in the next election, following FDR's New Deal Wave . . . and won. Then he repeated that success three more times before retiring a five-time mayor in 1941.

0 Comments

|

Visit Us

|

Resources

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed