|

The Horse Flu of 1872 Comes to Clay County, Minnesota

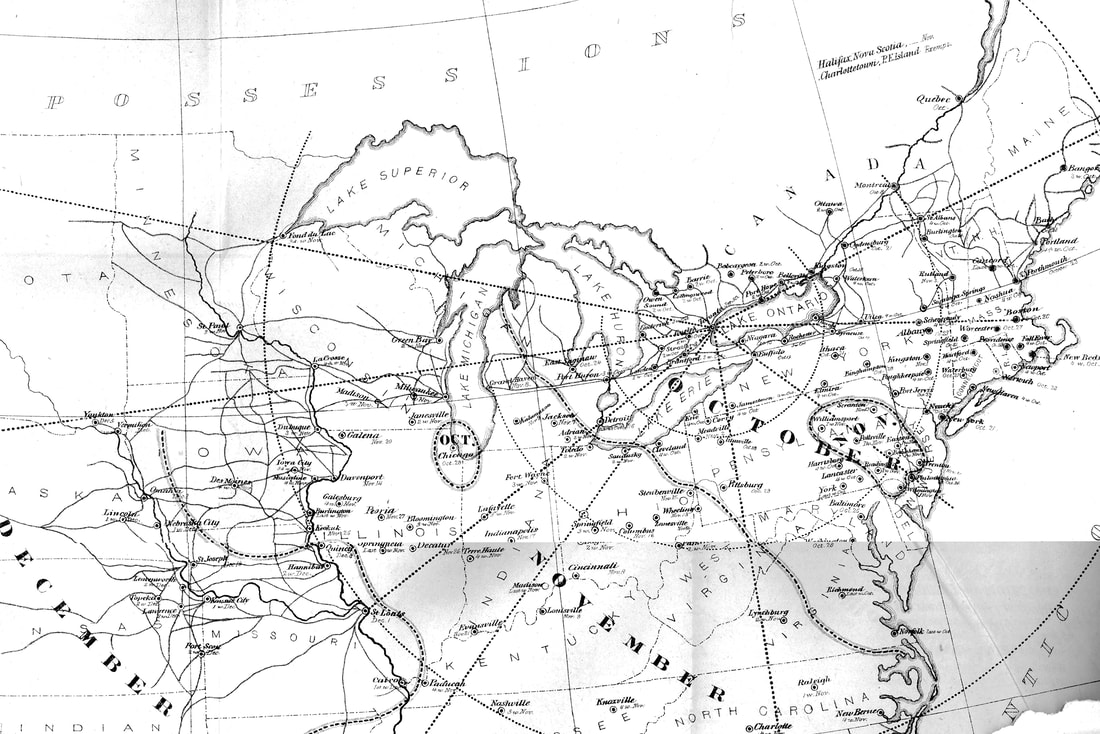

Davin Wait April 22, 2020 * * * * * * * * * * Life in the early years of Clay County, Minnesota, was far more dangerous than it is today. Tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and cholera confronted the limitations of public health, sanitation, and science in the 19th century. From 1872 to 1900, that spelled out a life expectancy of roughly 48 years and cemeteries where half of the community’s graves belonged to children 12 years old and younger. A quarter of them belonged to children younger than 12 months. It meant that Clay County families in the 19th century faced an infant mortality rate of 160.4 (number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births — the global high today is Afghanistan's 110.6). And if we look to the destruction of Native American populations that coincided with the expansion of Europe and the United States into the Americas — an estimated 90% population loss from pre-Columbian levels that reached its nadir in 1900 — we see an even more sobering look. However, the first true epidemic in Clay County’s history wasn’t really even an epidemic at all. It was a novel flu virus that local residents suffered only indirectly. It was the Great Epizootic, otherwise known as the Horse Flu of 1872, and it effectively ground America’s local, horse-driven economies to a halt. Horses experience influenza much like humans, so the Great Epizootic brought symptoms including runny nose and eyes, cough, fever, weakness, and chills to nearly all of the horses, donkeys, and mules in North America. The disease was first identified near Toronto at the end of September in 1872. Professor Andrew Smith of the Ontario Veterinary College believed the disease originated among pastured horses fifteen miles north of the city. By Friday, October 4, nearly all of the horses in Toronto’s streetcar and livery stables were sick. Two and a half weeks later it reached Boston and New York City. On Thursday, October 24, it was in Chicago. By the end of November, it was reported in St. Paul, Des Moines, New Orleans, Atlanta, and most of the cities between. An ill-timed shipment of horses destined for Governor Francisco Ceballos y Vargas brought the disease to Cuba. The isolation and landscape of Nicaragua finally stopped it just short of South America in September of 1873, an entire year after it had popped up in the Canadian countryside. In an 1874 report issued to the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Cornell veterinarian Dr. James Law estimated that 80-99% of horses, mules, and donkeys in North America had been struck by the disease. Roughly 1-2% of them died, with some urban areas reporting equine mortality up to 10%. It touched down in the Red River Valley in December, 1872, where it was first reported by Glyndon’s Red River Gazette the day after Christmas: The horse disease has finally reached this place and Moorhead. So many of the stage horses on the line between Fort Garry and Breckenridge are sick, that the stages between Moorhead and Breckenridge have been taken off entirely, and from Moorhead to Fort Garry fiery untamed oxen careen over the prairie with the mail at the rate of a mile and half an hour. The McDonald brothers, of Glyndon, started last Tuesday from Moorhead with five teams loaded with tea for Fort Garry, but their teams were taken sick on the road, and after getting as far as Frog Point, they were compelled to give up the trip, and put their horses under treatment. One of the brothers remained to take care of the teams, and the other two took Foot and Walker’s line back to Glyndon. The only case of epizootic we have heard of yet in Glyndon is that of one of Hendrick’s ponies, which now exhibits all the symptoms, but in a mild form. While recent research from Dr. Michael Worobey at Arizona State University has connected the Great Epizootic of 1872 to the novel H1N1 strain of influenza that wreaked havoc around the globe during World War I, in its own time the disease was primarily an economic and technological disaster. Though much of the United States had already adopted steam engines, railroads, and telegraphs, draft animals like horses and mules were still vital to the American economy. Agriculture, transportation, and communication very much depended on the health of these animals. When the flu struck, local economies ground to a standstill for weeks at a time as laborers confronted the inadequacies of human power compared to horsepower. One of the most striking examples of this occurred in Boston, where a massive, two-day fire beginning on November 9 took shape in the absence of the horsepower necessary to pull the fire departments’ engines. Louis Sullivan, a student at MIT at the time of the fire, recalled a fire engine arriving too late to a burning warehouse: "The people at curbside waited, but still no firemen came. Fire engulfed the warehouse, then its roof and floors collapsed. Finally a fire engine arrived, too late. Men, not horses, pulled the apparatus." The city lost 776 buildings over 65 acres of land and nearly $75 million in property value. As epidemics (or epizootics) often do, the devastation of the Horse Flu of 1872 prompted a revitalized effort toward social and technological innovation. Here on the edge of the frontier, railroads and settlement immediately changed the landscape and ecology. Innovation in healthcare and medicine came, as well, it just moved a little slower. * * * * * * Want to learn more about the Horse Flu of 1872 in Clay County? Become an HCSCC member and dig into our Summer 2020 newsletter!

4 Comments

Join HCSCC Programming Director Markus Krueger for a brief video tour of HCSCC's local exhibition, "War, Flu, & Fear: World War I and Clay County." The exhibition explores Clay County's experiences during a time marked by global war, disease, and paranoia. It's a sobering look at perhaps Clay County's darkest hour, but brighter and better years followed. |

Visit Us

|

Resources

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed